Excerpt from new Hank Greenberg book: Baseball finances during Depression

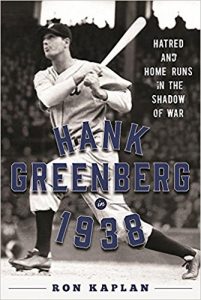

The following is an excerpt from Ron Kaplan’s new book, Hank Greenberg in 1938: Hatred and Homers in the Shadow of War

The following is an excerpt from Ron Kaplan’s new book, Hank Greenberg in 1938: Hatred and Homers in the Shadow of War

******

Hank Greenberg’s salary for 1938 was $30,000, a bit more than $500,000 in 2016 dollars or just about the major-league minimum these days. And he had to fight to get a $5,000 raise over the previous year, which he considered his best season: 40 home runs, a major league–leading 184 RBIs, and a slash line of .337/.436/.668. But this was a time before free agency, when players were bound by a “reserve clause” that made them the property of the teams with which they signed until they retired or were traded, sold, or released. And there were always hungry youngsters waiting in the wings, ready to step in and take a roster spot—even in Greenberg’s case. Sure, a player could hold out for more money, but he was taking a big risk.

This was especially true during the Depression. There was an issue of public perception that management liked to hold over a player’s desire for a raise, no matter how well-deserved it might have been.

The average salary for a lawyer in 1935 was $4,272. For doctors it was $3,695, while college professors might have expected to draw $2,666. Industrial workers pulled down about $1,200. Farmers—many of whom had seen their crops decimated by hostile climatic conditions, including the famous dust storms—were on the low end of the scale, barely pulling in $300 per annum. How would they react to someone holding out for thousands of additional dollars when they had a difficult times literally just trying to live from day to day?2

President Roosevelt signed the Fair Labor Standards Act in June 1938, setting a minimum wage, a maximum number of hours per work week, and limits on child labor, among other things. The legislation was actually enacted in October of 1938, but it would take some time before workers would see the benefits and perhaps use a little of that extra money into leisure activities such as going to a ballgame.

Even though the recovery had slipped due to the 1937 recession, baseball actually saw record attendance in 1938. Writing for the Associated Press at the end of the season, Hugh Fullerton gave Greenberg a nod as one of the reasons:

“Add together that exciting National League pennant race, the Yankees’ slow start in the American League, the unusual interest aroused by such individual feats as Johnny Vander Meer’s two no-hit pitching performances and Hank Greenberg’s threat to break the home run record and you arrive at the fact that major league baseball attracted more fans during the 1938 season than ever before.”3

Unfortunately, Greenberg’s hometown supporters were unable to join in the fun. The Tigers would see their attendance drop from 1,072,276 in 1937 to 799,557, the largest decline in the league but still the second highest total attendance in the AL.

Despite all the threatened negative publicity, baseball fans seemed willing to give Greenberg and his co-workers a little extra latitude.

“There should have been resentment toward these men, who were making a good living by playing a boy’s game at such a difficult time. Just the opposite was true,” according to Joe Falls, a veteran sportswriter for several Detroit newspapers. “The fans, needing an outlet from all the worries of the day, embraced them as heroes. At least they could go to the ballpark and know there was still some normality in the world.

“An afternoon at Navin Field, with Gehringer shooting a double into the right-field corner and with Greenberg, up next, putting one into the left center-field bleachers, was a reason to feel good,” he continued, referring to the previous name of the Tigers’ ball park. “It was a reason to feel hopeful, too; if the ball club could survive, why couldn’t the people of the city? The banks could close, but not the ballpark.”4

When Greenberg arrived in Detroit for his first full season in 1933, he lodged at the Wolverine Hotel for $8 a week. “They gave you a room with a bed but no closets. . . . [W]e just hung our clothes on the curtain rod in the bathroom,” where players could save a few bucks on cleaning bills by using the shower to steam their clothes.5

He also recalled what passed for extravagance in those days: dinner and live music at the Leland Hotel, a nice twenty-minute walk from the ballpark (and where he resided during the season in subsequent years), cost $1.25. Plus the twenty-five cent tip he might leave to impress an attractive waitress.