Q/A with Jerry Reinsdorf: The Brooklyn kid who grew up to own White Sox

It was a bright spring day in Glendale, Ariz. Holding his cigar, Jerry Reinsdorf sits back in his chair on the veranda outside his office.

It was a bright spring day in Glendale, Ariz. Holding his cigar, Jerry Reinsdorf sits back in his chair on the veranda outside his office.

The White Sox owner overlooks the massive spring training complex his team shares with the Los Angeles Dodgers. There is some irony in that association.

Never in Reinsdorf’s wildest imagination did the kid from Brooklyn, who grew up as a passionate Dodgers fan going to games at Ebbets Field, ever dream that he would become a MLB owner and a business partner with his childhood club that eventually broke his heart. More on that later.

“Infinity to 1,” said Reinsdorf of the odds of this dream actually coming true.

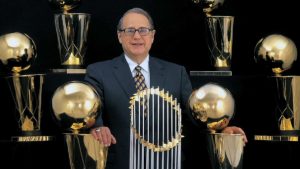

Indeed, it has been a remarkable run for Reinsdorf. One of the most respected owners in baseball, he experienced his ultimate dream when the White Sox won the 2005 World Series. As owner of the Chicago Bulls, he oversaw the franchise during their six NBA championship dynasty in the 1990s. In 2016, Reinsdorf was enshrined in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

At age 82, Reinsdorf shows no signs of slowing down. I have known him for more than 30 years, dating back to when I covered the White Sox for the Chicago Tribune in the 1980s.

At age 82, Reinsdorf shows no signs of slowing down. I have known him for more than 30 years, dating back to when I covered the White Sox for the Chicago Tribune in the 1980s.

I always have found Reinsdorf to be one of the most engaging, funny, thoughtful and honest people in sports. He didn’t disappoint in this interview for JBM. He discusses growing up in Brooklyn; early memories of Sandy Koufax; his road to owning the White Sox; and his special friendship with Bud Selig.

Also, please read all the way to the end of the interview, where Reinsdorf shares a terrific story of what it means to be Jewish.

*****

What was it like to grow up in Brooklyn right after WWII?

Recently, I did in an interview with someone and he asked, “What was it like to be from Brooklyn?” I said, “Well, if you’re not from Brooklyn, you can’t understand it.”

When two people from Brooklyn meet, the first question always is, “Where did you go to high school?”

Brooklyn was a state of mind. Brooklyn was a separate city until the late 1890s. So when I came on to the scene in 1936, there were still people alive who remembered Brooklyn merging into New York, and they still were angry about it. Brooklyn had its own downtown, newspaper, baseball team and for a long time its own water.

There was a great pride. We did not consider ourselves New Yorkers. Manhattan was New York.

You grew up in a one bedroom apartment. What was that like?

I didn’t know it was bad. My brother and sister shared the bedroom with my mother and father. I slept in a rollaway cot in the hallway. There was a benefit to sleeping in the hallway. When we got TV in 1950, I could look from where I was into the living room and watch TV. I attached a string to the plug. When I found myself dozing off, I would pull the plug. I think that was the first remote control.

We weren’t poor. We were just lower middle class. There was always food, clothes, but no car.

Did you grow up much with Judaism?

Yes and no. We never had trafe in the house. I had to be Bar Mitzvahed. But we didn’t go to synagogue on a regular basis. It was more growing up with a Jewish culture.

Did you have an awareness of Jewish players growing up?

Oh yeah, Hank Greenberg, Sid Gordon, Cal Abrams and others. I remember asking Al Rosen, who was the better third baseman, you or Sid Gordon, and Al broke up with laughter because he was the greatest third baseman of all time while Sid was a journeyman. Gordon was a Jew from Brooklyn who played for the Giants. I never rooted for him. They once had a day for him in Ebbetts Field. I was ticked off about that.

The Dodgers had Cal Abrams. Couldn’t run. We had Jake Pitler, who was the first-base coach for many years.

I think Jews are always aware of Jews. You’re always interested to find out if someone is Jewish. If someone Jewish did something bad, I remember my mother would say, “Oy, he has to be a Jew.”

What were your first memories of Jackie Robinson?

I actually went to the first game Jackie wore a Dodger uniform in Brooklyn. In 1947, the Dodgers played the Yankees in a preseason game in Brooklyn before the season opener. It was that game, not April 15, that he first put the uniform on.

Back then, the significance of his color didn’t sink in to an 11-year old. I just knew the Dodgers had two rookies coming up: Jackie and Spider Jorgensen, a third-baseman. We just wanted to see them play.

I don’t really remember what he did that day or much about that game. Maybe I should revise history to tell a better story, but the fact of the matter is all I cared about, was he going to be any good?

The first time it dawned on me that something more was happening was when I asked my friend, Lester Davis, who was African American, who is your favorite player? He looked at me like I was an idiot and said, “Jackie Robinson, of course.”

I said, “Oh yeah, that’s right.”

It quickly became apparent that Jackie could play. He wasn’t the best player I ever saw, but I always say he was the most exciting. He could do everything. He could run, bunt, steal bases, and hit the occasional home run. I vividly remember Jackie jockeying back and forth on first base, messing around with the pitchers.

One maneuver Jackie loved was after hitting a single to rightfield, he would take a big turn around the bag. Very often, the rightfielder would throw behind him, and Jackie would race to second. Joe Torre once said the most exciting thing about Jackie Robinson is that you couldn’t tag him out. He was incredible to watch in rundowns.

What are your early memories of Sandy Koufax?

Koufax and I are the same age. He came up in ’55. They hardly ever used him. He couldn’t throw the ball over the plate. He did have one great start in ’55. The Dodgers were starting to slip, and I think he pitched a shutout.

He didn’t do much for a long time. I remember asking Bob Shaw of the White Sox, who beat Sandy 1-0 in Game 5 of the 1959 World Series, “What was it like to be down 3 games to 1 in the World Series and have to pitch against Koufax?” He said, “In 1959, he wasn’t Sandy Koufax.”

Did you get to meet him or know him?

Yes, he’s a very solid guy. He and I shared a common friend, Sid Young. He knew Sid longer than I did. Sid died, and Sandy flew out from Florida to the memorial service in Santa Monica, as did a bunch of Sid’s friends. Sandy spoke, and I saw a picture of Sandy when he was among his friends from high school. He was not reserved there. He was outgoing, and funny.

I usually see him at the Hall of Fame. It always amazes me that with all these Hall of Famers, if Sandy’s there, everyone runs to him to get his autograph. There’s a certain mystique about him.

When the Dodgers left Brooklyn, were you crushed, heart-broken?

Absolutely. I’m still ticked. There’s no way that an iconic franchise should have been allowed to move. They should have expanded to West Coast. Three years later, they expanded anyway.

Once the Brooklyn players were gone in Los Angeles, I rooted against the Dodgers, and I still do to this day.

But you share a spring training complex with the Dodgers in Arizona?

So what? I’m a business man.

What are the odds of a one-time Brooklyn Dodgers fan owning a baseball team?

I don’t know. Infinity to 1. It never was on my mind. The only goal I had is that I wanted to own a car. And I wanted to be a lawyer since I was in eighth grade. Perry Mason, that’s what I thought law was.

When did you start to think you could own a team?

When did you start to think you could own a team?

It was 1975. Somebody ran an ad in the Wall Street Journal. It was advertising for limited partners to buy a team. So I called him. He was going to buy the Giants and move them to Toronto. He wanted $500,000. I said, OK. It didn’t work out. Years after that, he tried to buy the Indians, and that didn’t work out. And he tried to buy the Mets, and that didn’t work out. I was going to be an investor in each of those cases.

I was taking a shower one day, and I started thinking maybe it is good these deals didn’t happen. What’s the point of investing in a team that plays in a city where you don’t live? Why did I want to be a passive investor? That’s not how I operated in my other deals. The thought occurred to me that Bill Veeck, who headed the group that owned the White Sox, never owned a team for more than five years. I asked my friend Allen Muchin to make contact with Veeck to see if he would be willing to sell the White Sox. And it happened from there.

How would characterize your relationship with Bud Selig?

We’re good friends, but we often disagree. I wish he would have listened to me more. I was not in favor of him becoming commissioner. At the time, he still owned the team. I didn’t think that was a good idea. However, once he sold his team, I was all for him.

You guys have lunch every Saturday in Arizona in the winter. If someone sat in on that conversation, what would they hear?

It depends on the time. It’s always about baseball, politics and gossip.

How did you feel when Bud got in the Hall last year?

It was great. He should have gone in sooner.

How did you feel when Selig was the person who handed you the World Series trophy in 2005?

How did you feel when Selig was the person who handed you the World Series trophy in 2005?

I had to think in advance what I was going to say. As he presented me the trophy, he started to move away. I said, “Stay.”

I said, “For 25 years, I’ve been asking you, “Why did you get me into this mess? I’ll never ask you again.”

That’s always been my line as I’ve seen payrolls skyrocket and it gets harder to survive. It’s a stupid business. So when anyone signed players to what I thought was an insane contract, I’d always say to him, “Why did you get me into this?”

Through the years, what sense did you have that Jews were proud of what you have accomplished in sports?

There’s one rabbi in Chicago. He may have died because I haven’t heard from him lately. Every time I did something unpopular, he would write to me say, “You’re embarrassing the Jews.”

Then again, I get a lot of letters from people who are proud of me being Jewish.

I’ll tell you my best story about what it means to be Jewish. My first job out of law school was going to be with the IRS. My friend, Sandy Takiff, and I decided to go Washington to take the DC bar exam. On Memorial Day, 1960, we’re in a car, and it’s pouring rain. We’re on the Ohio Turnpike and the car breaks down. We get towed into the town of Fremont, Ohio. Nothing is open. We didn’t know what to do.

Sandy says to me, “My uncle told me if you ever get stranded in a small town, look for the head Jew.” So we found a phone book and looked for a synagogue. I don’t know who answered the phone, but she said, “Let me call my uncle.” A little while later, we get a call on the pay phone we were at. It’s her uncle, Harold Danzinger. He said, “Let me take you guys home and we’ll figure out what to do with your car.” He pulled up in this huge black Chrysler Imperial. Biggest car I’d ever seen.

He took us home. He was very religious. In his home, he had one kitchen for Passover and one for the rest of the year. We had been up all night. They fed us. He got hold a friend at a Chevy dealership, but they didn’t have the parts we needed. So we stayed there for 2, 3 days, and they took great care of us.

All because we were just two Jewish kids from out of town. So that’s what it means to be Jewish.