Q/A with author of new book on Hank Greenberg historic ’38 season: A Jew tries to break Babe’s HR record

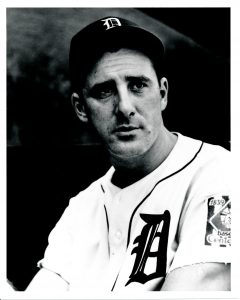

In 1938, Detroit Tigers first baseman Hank Greenberg enjoyed one of the finest seasons of his Hall of Fame career, racking up a .315 batting average and a .683 slugging percentage, knocking in 147 RBIs, and leading the majors (and setting career highs for himself) with 143 runs, 119 walks, and 58 home runs.

In 1938, Detroit Tigers first baseman Hank Greenberg enjoyed one of the finest seasons of his Hall of Fame career, racking up a .315 batting average and a .683 slugging percentage, knocking in 147 RBIs, and leading the majors (and setting career highs for himself) with 143 runs, 119 walks, and 58 home runs.

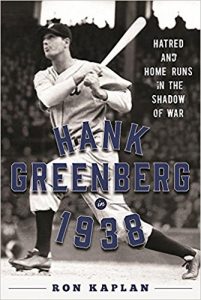

Well, maybe “enjoyed” isn’t the right word. As Ron Kaplan recounts in his new book, Hank Greenberg in 1938: Hatred and Home Runs in the Shadow of War (out April 25 via Sports Publishing, an imprint of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.), the 1938 season was a brutal grind for baseball’s first Jewish superstar. Playing for an uninspired Tigers team that spent most of the season struggling to raise itself above the .500 mark (and eventually finished in fourth place, 16 games behind the American League champion New York Yankees), the “Hebrew Hammer” nonetheless became the daily subject of intense press scrutiny, thanks to his steady assault on Babe Ruth’s decade-old record of 60 home runs in a single season.

Even more distracting than the pressure that came from chasing Ruth were the dark clouds gathering over Europe. Adolf Hitler had taken direct control of Germany’s military in February of 1938; German troops marched on Austria the following month, and began engaging in maneuvers along the borders of France and Czechoslovakia during the summer. Already deprived of many of their civil liberties under the Nazi regime’s Nuremberg Laws, and openly harassed in the streets of their cities and towns, many German and Austrian Jews attempted to flee, only to find that most neighboring countries had closed their borders to Jewish refugees.

The United States wasn’t much more welcoming. With the country still digging itself out of the Great Depression, the idea of relaxing U.S. immigration quotas to accommodate Jewish refugees from Europe found little favor among elected officials or their constituents. Kaplan refers to one Gallup poll conducted in November 1938 — two weeks after the Kristallnacht pogroms in Germany, Austria and the Free City of Danzig — which revealed that, while 82.3 percent of Americans polled disapproved of the Nazi treatment of Jews, only 21.2 percent of the respondents thought that the U.S. should allow a larger number of Jewish exiles into the country. “Many Americans became concerned about possible additional economic drains if the displaced were allowed to settle on U.S. soil,” Kaplan writes.

For Greenberg, the son of Jewish immigrants from Romania, simply playing the game of baseball to the best of his abilities was no longer an option. “I didn’t pay much attention to Hitler at first or read the front pages, and I just went ahead and played,” Greenberg would later write in Hank Greenberg: The Story of My Life. “Of course, as time went by, I came to feel that if I, as a Jew, hit a home run, I was hitting one against Hitler.”

Kaplan, author of the books The Jewish Olympics: The History of the Maccabiah Games and 501 Baseball Books Fans Must Read Before They Die — as well as the host of Ron Kaplan’s Baseball Bookshelf (http://www.ronkaplansbaseballbookshelf.com) — paints a vivid picture of Greenberg’s 1938 season, placing the slugger’s accomplishments squarely within the cultural and political context of a deeply foreboding and fateful year.

Here is a JBM Q/A with Kaplan.

Here is a JBM Q/A with Kaplan.

Short Takes

On whether or not anti-Semitism motivated opposing pitchers to pitch around Greenberg as he neared Ruth’s home run record:

“It’s hard to know what’s in another man’s mind. But did the majority of the pitchers think about the fact that the guy up at bat was Jewish? I don’t think so.”

On Greenberg’s relationship with noted anti-Semite Henry Ford:

“It’s not like with today’s athletes, who are more politically outspoken; in those days, you kept your head down and kept your mouth shut. And I think as much as Greenberg stood up for himself on the field, when it came to defending himself against anti-Semitic canards, outside of that he wanted to keep a low profile.”

On Hank Greenberg as an American hero:

“Over time, I became more fascinated with Greenberg not just as a player, but as an American citizen. The fact that he went into the service at that critical juncture in his career, and that he was fully prepared to never play again — and unlike a lot of players who served, he was not in it for morale-boosting.”

The JBM Interview

The JBM Interview

There have been some very good books written on Hank Greenberg in recent years, such John Rosengren’s Hank Greenberg: The Hero of Heroes and John Klima’s The Game Must Go On. What inspired you to add to the Greenberg canon?

Well, if you want the truth [laughs], I did a book about a history of the Maccabiah Games for Skyhorse; and based on that, one of the editors there asked me if I would be interested in doing this book. I was actually in the planning stages of another baseball book at the time, but this fell into my lap.

And they specifically wanted you to focus on Hank’s 1938 season?

Yes. It’s kind of amazing the parallels you can draw between what was going on then, in terms of the way that the status of refugees was being handled, and what’s going on now.

Not to mention the international rise of anti-Semitism.

In those days, I wouldn’t even call it a rise — sad as it is to say, that was the norm back then. It’s been put down over the course of decades, but unfortunately it does seem to be on the rise now. But back then, there were still listings in the Want Ads saying that they specifically didn’t want Semitic-looking women for secretarial jobs, and people didn’t want to rent apartments or houses to Jews. That was a real thing back in the thirties, and it was exacerbated by the Depression. Everyone was looking for someone to blame for the Depression, and the Jews always seem to be a convenient scapegoat.

One can’t talk about Hank’s 1938 season without wondering whether or not anti-Semitism kept him from breaking Babe Ruth’s home run record. Some players and writers have claimed that opposing hurlers actually pitched around him during the last month of the season. Hank refused to give much credit to this theory — but then, it wasn’t exactly his style to make such claims. Ultimately, what do you think?

It’s hard to know what’s in another man’s mind. But did the majority of the pitchers think about the fact that the guy up at bat was Jewish? I don’t think so. In the appendix of my book, I include a list of the pitchers he faced during that last month of the season, and I include their walks per nine innings ratio, to see if it was higher or lower during these games than normal. And I think everything cleaves pretty close to what they were doing during the rest of the season with everybody else. When you get to September, the days get shorter, the weather gets worse. They played a lot of double-headers to make up for games that had been called earlier in the season, and some of those makeup games ended early because of darkness. So Greenberg lost a lot of at-bats because of that.

Harry Eisenstat pitched for the Tigers in 1938, giving the team two Jewish players on their roster. Eisenstat was only 22 at the time; tell us a bit about his and Hank’s relationship.

Greenberg took Eisenstat under his wing. He gave him advice on and off the field, taught him to dress like a big-leaguer, and told him not to play cards with the other players on the train — if you lose, that’s fine, but if you win you’re going to start hearing [anti-Semitic] stuff!

Let’s talk about Hank’s relationship with Henry Ford. It’s pretty weird, in retrospect, to read that Detroit’s greatest Jewish sports figure worked during the off-season for Detroit’s most high-profile anti-Semite…

I thought that was so bizarre, too. But look — in those days, you needed an off-season job, and Hank probably wanted to stay in Detroit. It seemed like a window-dressing job, like when they bring a ballplayer out to a car dealership to just glad-hand people. I spoke with Ira Berkow about that, because he worked on Greenberg’s memoir; I met him during the course of researching the book, and I asked him, “How could Hank Greenberg work for Henry Ford, however tangentially?”

But, basically, this what you did in those days. It’s not like with today’s athletes, who are more politically outspoken; in those days, you kept your head down and kept your mouth shut. And I think as much as Greenberg stood up for himself on the field, when it came to defending himself against anti-Semitic canards, outside of that he wanted to keep a low profile.

And from Ford’s perspective, having the Tigers’ most popular player working for him in the off-season was clearly a good PR move, regardless of how he actually felt about Jews.

Yes. Ford was definitely the type to say things like, “Some of my best friends are Jews!” [Laughs] When Germany gave Ford the Grand Cross of the German Eagle in 1938, there was a big hue and cry that he should give it back, that his acceptance of the award indicated support for the Nazis. And Ford responded by saying that there were hundreds of Jews employed in his plants — “and if the turnover among them is sometimes comparatively high, it is indicative of their ambition to improve themselves.” A total back-handed compliment!

Hank ended his playing career before you were born. Growing up as a baseball fan, and a Jew, what were your early impressions of him?

Hank ended his playing career before you were born. Growing up as a baseball fan, and a Jew, what were your early impressions of him?

Well, when I was a kid, it was all about Sandy Koufax — he was the one who didn’t play on Yom Kippur in 1965. When you’re that young, you’re not really a student of the game. But as you drift more towards the literary and pop cultural aspects of the game, you start going, “Okay, who else is Jewish?” Over time, I became more fascinated with Greenberg not just as a player, but as an American citizen. The fact that he went into the service at that critical juncture in his career, and that he was fully prepared to never play again — and unlike a lot of players who served, he was not in it for morale-boosting. He did play a little baseball in the service, but he didn’t like it. He thought the level of play was so inferior, what was the point?

I loved learning that, for all of Hank’s impressive ability, that he was also superstitious about wearing certain neckties to the ballpark when he was hitting well. Were there any other notable quirks about him, as a player or a person, that you discovered in your research?

Not really; that was the big one. He was really very dignified. He was brought up in a family that, like a lot of Jewish families at the time, insisted that their kids make something of themselves. And he did — and he was a success after his playing career, too; he was a success in the front office, and a success after he left baseball altogether.