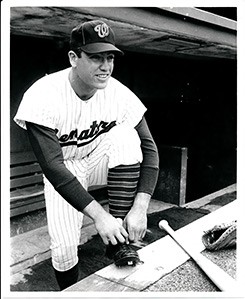

Q/A with Mike Epstein: Proud of being known as ‘Super Jew’

Dubbed with one of the game’s most memorable nicknames, “Super Jew,” Mike Epstein was a hard-hitting first baseman for four major league clubs, most prominently the Washington Senators and the Oakland A’s. Over four seasons running, his home run totals were 30, 20, 19 and 26, and he won a World Series with the A’s in 1972. He hit three home runs in one game; another time, he hit four homers in four straight at-bats over two consecutive games.

He burst on to everyone’s radar as a farmhand with the Baltimore Orioles’ Rochester Red Wings. Epstein earned the International League’s 1966 Most Valuable Player award, and nearly the Triple Crown, with a .309 batting average, 29 home runs and 102 runs batted in. Eventually, he had his best year in 1969 under the eye of first-year manager Ted Williams, hitting 30 homers for the Washington Senators in 1969.

After a successful post-baseball business career, he returned to the sport as an instructor and has been acclaimed for preaching “rotational hitting”: a weight shift emphasizing the entire body, rather than the arms and legs alone, to swing. He and his son Jake run Mike Epstein Hitting in suburban Denver.

Short Takes

On playing for Ted Williams, one of baseball’s legendary hitters:

“To meet Ted Williams at that time, it was: This guy could help me. Ted just knew, by looking at somebody, whether you were doing something right or wrong. I was all ears.”

“We had our ups and downs in our relationship when I was playing. Years later, we’d just talk hitting. He gave me the framework in which to work; otherwise, I couldn’t have done it.”

On learning in September 1972 of the murder of Israeli Olympians:

“We were shocked. How could something like this happen? Don’t people remember? Don’t they have any sense of history?”

On Jewish pride:

“It’s an honor to be a Jew and to have been afforded the opportunity – the luxury, actually – of being able to play on that stage and have a positive effect on other Jewish people. You see the contributions that cultures have made to the human race, and you look at the notable achievements of Jewish people – what’s there not to like?”

On nearly homering in five consecutive at bats – something that’s still never happened in the majors:

“One thing about Ted is: He knew all the records, and no one’s ever done five. In later years with Ted, I said, ‘You know that ball was fair.’ He sort of smiled and said, ‘Doesn’t make any difference now.’ ”

The JBM Interview

As a kid, were you drawn to baseball by your dad?

Epstein: No; in those days, dads worked and moms took care of the house. My dad [Jack] wasn’t a sports person, but my uncles were. Uncle Irving [Udoff] – my father’s sister’s husband – had three daughters. He wanted a son desperately and never got one, and I was the only son, so he bought me my first pair of spikes. He didn’t have much money. I was about nine years old, and the spikes were so big that I had to stuff them with paper on the end – but that’s all he could afford. I remember walking on the dirt with the spikes. You know how it turns up the ground? I said, “Man!” Then I walked on some pavement and I said, “Wow!” It was like being in the big leagues.

He bought me my first glove. He played catch with me all the time. My dad never did. I got a football scholarship to Cal.-Berkeley; Marv Levy was the coach and Bill Walsh was an assistant coach. In fact, Bill was the one who recruited me.

The first time my dad saw me play football was at Berkeley. Baseball-wise, he never took an interest. At the [1972] World Series in Oakland, he and my mom flew up. They were sitting behind our dugout. When my name was announced, he stood up and turned around to the crowd and said, “That’s my son. That’s my son.” Ahhh. [Deep sigh.] We never had that common bond, and that’s so important. I have one son and two daughters. My son, Jake, and I have an unbelievable relationship – really, really close. He was an All-America at the University of Missouri, and he played in the Angels organization a short while. He didn’t particularly like professional baseball. He runs the hitting company that I own. He grew up with me coaching him to amateur national championships. It’s been a great run.

How did you get the nickname “Super Jew”?

[Opposing coach] Rocky Bridges gave it to me. I was playing at Stockton [in the minor leagues, in 1965], and I came up one night and hit one over the light tower in right-center. When I was trotting out to first base when the inning was over, he went by and said, “You really got a hold of that one, Super Jew!” The clubhouse kid heard it, because he was picking up the bat at home plate, and the next day when I came into the locker room – they usually have your number or name on your sweatshirts and underwear and stuff like that, and he had Super Jew written on them. So when I came to the big leagues, that’s what my nickname was. There was a Jewish writer with True magazine who wrote an article and said, “Watch out, world, here comes Super Jew.”

How did that strike you?

To me, it was an identification, a nickname, like the Say Hey Kid, the Duke of Flatbush. A lot of times, when I sign autographs for people, they’ll ask: “Would you put Mike ‘Super Jew’ Epstein? I’m proud of it.

What was it like for you to come to spring training in 1969 – entering your second full year with the Washington Senators, your third full year in the major leagues – and there’s your manager, Ted Williams, maybe the greatest hitter ever?

I broke in to the big leagues when hitting was at its lowest ebb in a long time. [After 1968], lowering the mound took the leverage away from pitchers. … I’d come off two subpar seasons, and your confidence gets shaken and you say, “Wait a minute.” I was supposed to be the next Mickey Mantle, the next this, the next that, and nothing’s panning out. So to meet Ted Williams at that time, it was: This guy could help me. Ted was not a hitting instructor. Ted couldn’t really tell you what to do. He just knew, by looking at somebody, whether you were doing something right or wrong. I was all ears. In fact, one of the Topps cards shows Ted and me and says, “Ted Shows How.”

We had our ups and downs in our relationship when I was playing. It wasn’t until later on, when all the pressure was off him and me, that I’d be down in Florida four times a year on business and would spend the weekends with him and we’d just talk hitting. He’d say, “You know a lot more now.” I was able to translate what he was able to say into drills that would implant that movement in a hitter. The technique is universal; the style is personal. He gave me the framework in which to work; otherwise, I couldn’t have done it.

What prompted you and your Oakland Athletics teammate Ken Holtzman to wear black armbands in September 1972, after the terrorist murders of the 11 Israeli Olympians in Munich?

Empathy. We were shocked. I mean, we’re Jews. You don’t have to go to shul all the time to be a Jew. You take from the religion what’s important. We were both bar mitzvah’ed and came from families with religious roots, so we just took that to heart. We just sat there. In fact, we were dumbfounded. We were in Chicago at the time to play the White Sox, and we walked around town for a few hours. We were just in a daze, like: How could something like this happen? Don’t people remember? Don’t they have any sense of history? So we decided: To memorialize the event, we’d wear the black armbands. Lo and behold, wouldn’t you know it, Reggie Jackson got a hold of some black material, and he put a black armband on, too, as a way of getting some attention.

In fact, earlier that season, you had a third Jewish player on the A’s: Art Shamsky.

I’ve got a picture somewhere of [the Yankees’] Ron Blomberg, Art Shamsky, Kenny Holtzman and myself. It was in New York. It’s an honor to be a Jew and to have been afforded the opportunity – the luxury, actually – of being able to play on that stage and have a positive effect on other Jewish people. I did an autograph session in 1999, on the 30th anniversary of Ted’s coming here [to Washington], and at least four or five people came up and said, “We named our son after you. We were such big fans.” You don’t realize it when you’re playing and then, when you’re out, you’re able to look at everything that happened and see the effect you had on people. I did the things I thought were right, according to what my parents would think was right, Jewish people would think is right.

What do you remember of your four home runs in four consecutive at bats with the A’s in 1971?

I actually had five consecutive home runs. The umpire called the fifth one foul. It was way over the rightfield foul pole, and it curved after it went over. I trotted down to first base and I’m seeing it all the way. It was a fair ball. Bill Kunkel was the first-base umpire. [Another] day, I come to home plate, and he says, “Mike, I may have missed that.” It was in Oakland, against the Senators. Williams had traded me. I came up in the seventh inning, and he brings in the lefthander to face me, Jim Shellenback, and I hit a home run off him. The ninth inning, the game’s out of reach, and Ted brings in another lefthander to face me, Denny Riddleberger. I hit a home run off of him. The next night, Denny McLain is pitching against us. The first two times, I hit home runs to the right-centerfield bleachers, so I had four. One thing about Ted is: He knew all the records, and no one’s ever done five. So it’s early in the game, and he brings in his closer, Paul Lindblad, the guy I’d been traded for. He hangs a slider to me, and I hit that ball down the rightfield line and it was fair [but called foul]. He’d gotten two strikes on me and threw me a really tough slider, and I struck out.

Talk about being “Super Jew.” You could’ve been the only guy to hit five homers in five consecutive at bats.

Tell me about it. In later years with Ted, I said, “You know that ball was fair.” He sort of smiled and said, “Doesn’t make any difference now.” He couldn’t tell because he was in the first-base dugout. It was a night game. I crushed that ball.

When you hit that ball, did you know it would have set a record?

No. I had no idea.

A friend of mine in Baltimore is a Jewish guy who grew up in Washington. As a kid, he was a Senators fan, but then became an A’s fan. Why the A’s? Because you were his favorite player, and after the Senators moved away from Washington, he followed you with the A’s rather than follow the Texas Rangers, the former Senators. Have you heard that kind of story before?

I have. I was at a birthday party here last night. The host’s wife died of cancer a few years ago, and my friend had asked: “Would you write a note to her? She was probably your biggest fan.” So I wrote her a story – that I’m sorry you’re not feeling well and that I understand you were one of my biggest fans so I want to tell you a story that I hope will bring a smile to your face.

So here’s the story: Spring training, 1971, we’re playing the Cincinnati Reds. Ted would always have a throng of reporters around. The Reds were taking batting practice, and I’d just like to sit next to him and hear what he says. These writers are asking questions, and all of a sudden this player pushed through the crowd.

He says, “Excuse me, Mr. Williams, I’m Pete Rose. Would you sign this ball for me?” Ted says, “Is it for you, Pete?” He says, “Yes, sir.” Ted was always accommodating, so he writes on the ball: To Pete Rose, a Hall of Famer for sure. Your pal, Ted Williams.

He must have gone back to the batting cage, because five minutes later the throng parts and a player comes through and says, “Excuse me, Mr. Williams, my name is Johnny Bench. Would you sign this ball for me?” He says, “Sure, John. Is it for you?” “Yes, sir, it is.” So he picks up a pen: To Johnny Bench, a Hall of Famer for sure. Your pal, Ted Williams.

I’m sitting there and I’m saying: Geez, I’d like to have a ball like that. So I reach in the ball bag and get a brand-new ball. I say, “Excuse me, Ted, could you sign this ball?” He says, “Is it for you, Mike?” I said, “Yes, sir, it is.” He picks up his pen. To Mike Epstein. Your pal, Ted Williams.

She got the greatest kick out of that. I was talking to her husband last night. She’d passed away shortly thereafter, and he said, “That was so nice of you to do that.”

*****

Hillel Kuttler is an award-winning features writer who writes on sports for the N.Y. Times, the JTA,Haaretz and other publications. He has covered the Olympics, the Super Bowl, NBA playoffs, the Maccabiah and European Maccabi Games, and from 1993-99 served as The Jerusalem Post’s Washington bureau chief. Hillel can be reached at hk@