L’dor v’dor: The annual re-telling of the Sandy Koufax Yom Kippur story

Once again, this story will be told countless times during Yom Kippur. More than 50 years later, Sandy Koufax’s decision, and the meaning behind it, gets passed down from generation to generation.

Once again, this story will be told countless times during Yom Kippur. More than 50 years later, Sandy Koufax’s decision, and the meaning behind it, gets passed down from generation to generation.

L’dor v’dor.

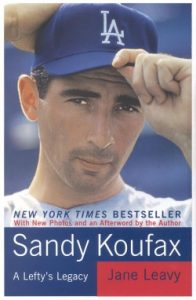

The passage below is from Jane Leavy’s excellent biography on Koufax. By the way, if you haven’t read Leavy’s book, you should. One of the best sports books ever.

********

In 1961, Yom Kippur began at sundown on September 19 and ended at sundown September 20. Koufax, as usual, fasted during the holiday. On the night of Sept. 20, though, he was on the mound and pitched the Dodgers to victory with a 13-inning, 15-strikeout, 205-pitch performance.

In 1965, the Dodgers had a big lead in the National League. It was announced that Oct. 6 would be game 1 of the World Series. Oct. 6 was Yom Kippur. They asked Koufax what he would do. He said,

“I’m praying for rain.” He also said he would consult a Rabbi. He never did.

Koufax told a Rabbi: ‘I’m Jewish. I’m a role model. I want them to understand they have to have pride.”

Thousands of Jews said they saw Koufax at various synagogues in Minneapolis. In fact, he never left his hotel room.

Don Drysdale, a Hall of Famer, pitched Game 1. He got bombed, giving up 7 runs. When the manager went out to pull him, he said, “Don’t you wish I was Jewish too?”

*******

Always loved that Drysdale line. I got to know Don when he was the White Sox play-by-play voice in the 1980s. Like Koufax, he was a Hall of Famer way beyond the pitcher’s mound.

*****

Countless other stories have been written about what Koufax did.

John Rosengren writing for SI.com did a piece last year on the 50th anniversary of that day. He writes:

When Koufax first announced his decision near the end of the regular season, it was a small item in most mainstream newspapers outside of Los Angeles. Dodgers owner Walter O’Malley, a Roman Catholic, even joked to reporters, “I’m going to ask the Pope to see what he can do about rain.”

But Koufax’s decision was instantly big news among Jews across the country. Michael Paley was a 13-year-old boy living in suburban Boston when he heard on the radio that Koufax would not pitch on Yom Kippur. The decision became the talk of his block. “It was the beginning of changed feelings about being Jewish in America,” says Paley, now a rabbi and scholar at the Jewish Resource Center of UJA-Federation of New York. “Because of Sandy, we were admired.”

Hillel Kuttler, a contributor to JBM, did a piece last year for Haaretz.

Koufax’s decision remains so profound, in fact, that a half-century later it still carries lessons for those raised neither with the sport nor in the United States.

London native Alexandra Benjamin teaches a course on Jewish history during the semester-long Tichon Ramah Yerushalayim international high school program. In discussions about the sometimes disparate pulls of secular and Jewish culture, she returns time and again to the Koufax decision.

“The reason the Sandy Koufax example works so well is that baseball is very much a part of American culture and he is Jewish,” Benjamin said. “At some point he had to make a choice.

“So some guy stayed home from work and it was Yom Kippur – he’s not the only one, but he’s a public figure,” she added. “Still today, that example is relevant, it works and it has impact.”

“Nobody said a word. Nobody thought a bad thing about him,” says Wes Parker, the first baseman on that 1965 L.A. team. “We respected him because he was doing it because of his religion. He was being true to himself.”

Second baseman and 1965 rookie of the year Jim Lefebvre agrees, saying while the media might have made a fuss about Koufax’s decision, the Dodgers simply didn’t care. “Whatever Sandy wanted to do, we were all on board,” he says.

“Most people admired Koufax for putting his religion before his job,” longtime Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully says. “I’m sure there were others who were furious, saying that he wasn’t that religious — and I don’t think he really was — but that didn’t make any difference. It was his decision, and everyone respected it. They understood.”

John Thorn, Major League Baseball’s official historian, was born to two Holocaust survivors in a displaced persons camp in Stuttgart, Germany, in 1947. The family immigrated to America in 1949, and Thorn fell in love with baseball. Thorn was in college when Koufax chose not to pitch on Yom Kippur.

“What struck me [about his decision], as an 18-year-old, was that America must be a very great place,” Thorn says. “That a Jew cannot only profess his faith openly but take a stance for his religion in opposition to the national religion — and baseball is America’s national religion.”