Meet ‘other’ Jewish Hall of Famer: Pirates owner Dreyfuss credited with conceiving first World Series

Next month, Bud Selig will become the fourth Jew to be honored with a plaque in the Baseball Hall of Fame’s hallowed gallery during induction weekend ceremonies in Cooperstown.

Next month, Bud Selig will become the fourth Jew to be honored with a plaque in the Baseball Hall of Fame’s hallowed gallery during induction weekend ceremonies in Cooperstown.

Two of the other three Jewish figures previously enshrined are obvious: Hank Greenberg and Sandy Koufax. Noted Jewish baseball historian Bob Wechsler correctly states that union leader Marvin Miller also should be there with them, but that’s a story for another day.

Besides Koufax and Greenberg, Selig now will be keeping company with another Jew who had an immense impact on the game.

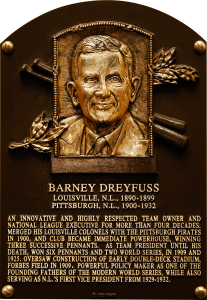

Meet Barney Dreyfuss, who was enshrined in 2008, a mere 76 years after his death.

Thankfully, the powers-that-be realized their oversight, because Dreyfuss’ credentials are considerable:

–He was a 32-year owner of the Pittsburgh Pirates from 1900-1932. His teams won two World Series and six National League pennants.

–He was a keen evaluator of talent; Pittsburgh’s Honus Wagner was one of baseball’s first superstars.

–He is credited with helping to create the modern World Series in 1903, merging the two rival leagues for what quickly became The Fall Classic, a centerpiece on the sports calendar.

–With baseball in chaos after the 1919 Black Sox scandal, his vast influence convinced his fellow owners to hire baseball’s first commissioner, Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Landis was among Dreyfuss’ honorary pall bearers.

–In 1909, he built Forbes Field. He had the vision to construct a two-tier stadium, one of the first modern facilities in baseball.

Sounds like a Hall of Fame career, doesn’t it?

Dreyfuss’ great-grandson, Andrew, said it best during the acceptance speech in 2008:

“He was a baseball man. He cared about the game, the players, the city. He understood that everyone had a share of it — the fans, the players, the owners. He worked hard at growing the game. He cared about winning. He lived the American dream, and he always said America is and always has been the land of opportunity.”

Indeed, Dreyfuss came a long way from humble beginnings. At age 24, he left his native Germany to move to Louisville. Knowing little English, he accepted an opportunity to work as a bookkeeper in his cousin’s bourbon distillery in Paducah, Kentucky.

Almost immediately, Dreyfuss was taken with the late 1880s version of baseball. He saw business potential in the game, and bought into the Louisville Colonels of the American Association.

The great Honus Wagner

In 1899, Dreyfuss made a deal to purchase a half-interest in the Pittsburgh Pirates. He brought some of his best Louisville players with him, including the great Wagner. More than 100 years before the age of analytics, Dreyfuss was known for relying on statistics and information on players. He always had the inside “dope” on prospects.

When Dreyfuss died in 1932, National League president John Heydler said, “He discovered more great players than any man in the game.”

No less than Branch Rickey said Dreyfuss was “the best judge of talent” he had ever seen.

Given Dreyfuss’ scouting touch, it hardly was a surprise that his Pirates vaulted to the top of the National League, winning three straight pennants from 1901-1903. Around the same time, the American League was created. Naturally, there was some conflict and considerable competition for players.

Dreyfuss sought to bridge the divide. After his team won the 1902 flag, he challenged an American League all-star team to face his Pirates. Pittsburgh won the series 2-1-1.

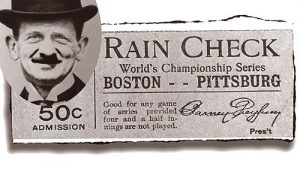

The following year, Dreyfuss issued another challenge to the American League winner, the Boston Americans.

In a letter to Boston owner Henry Killilea in August 1903, Dreyfuss wrote, “The time has come for the National League and American League to organize a World Series. It is my belief that if our clubs played a series on a best-of-nine basis, we would create great interest in baseball in our leagues and in our players. I also believe it would be a financial success.”

On Oct. 1, 1903 in Boston, Pittsburgh took a 7-3 victory in Game 1 of what was initially known as the World Championship Series. Dreyfuss, though, didn’t attend the game, and with good reason. It fell on Yom Kippur. He then watched Game 2 with his rabbi from Pittsburgh and a rabbi from the oldest synagogue in Boston.

On Oct. 1, 1903 in Boston, Pittsburgh took a 7-3 victory in Game 1 of what was initially known as the World Championship Series. Dreyfuss, though, didn’t attend the game, and with good reason. It fell on Yom Kippur. He then watched Game 2 with his rabbi from Pittsburgh and a rabbi from the oldest synagogue in Boston.

The Pirates were riddled with injuries, losing to Boston 5 games to 3. While disappointed, Dreyfuss still loved his team so much, he gave them his share of the gate. As a result, each Pirate received $1,316 compared to $1,182 for the Boston players. It marked the only time the losing team had a larger share than the winner.

Dreyfuss was right about his idea. After taking a year off in 1904, the World Series returned in 1905 with history being made annually in October ever since.

Dreyfuss continued to demonstrate his forward-thinking ways with his desire to build Forbes Field. He was convinced the Pirates needed a better facility to attract more fans to the increasingly-popular game. It didn’t come cheap; the price of $2 million was a big number in those days.

Many critics thought it was excessive, dubbing the new park “Dreyfuss’ folly.” Dreyfuss, though, knew he was making the right decision. It was confirmed with a full house for Forbes Field’s first game on June 30, 1909. Dreyfuss personally greeted fans at the gates, calling it “the happiest day of my life.”

Many critics thought it was excessive, dubbing the new park “Dreyfuss’ folly.” Dreyfuss, though, knew he was making the right decision. It was confirmed with a full house for Forbes Field’s first game on June 30, 1909. Dreyfuss personally greeted fans at the gates, calling it “the happiest day of my life.”

The Sporting Life wrote of Dreyfuss: “He had the mind to conceive and the courage to execute the plans which have given the world the grandest and most costly ball park in existence, deserves the greatest credit, highest praise, and utmost good fortune for his stupendous enterprise, which has ennobled the National League and enriched the city of Pittsburgh.”

The big year for Dreyfuss continued, as Forbes Field was the site of Pittsburgh’s first World Series title in 1909. The ballpark would be the Pirates’ home until June, 1970. Babe Ruth hit his final homers as a player there, and Bill Mazeroski belted the World Series-winning blast over its wall in 1960.

Dreyfuss’ major influence was seen again in the wake of the Black Sox throwing the 1919 World Series. The scandal forced baseball to come up with a new way to govern the game. There were several proposals, but Dreyfuss pushed for an independent person, a commissioner, who would be given complete authority. And he wanted Landis. He believed the judge’s integrity wouldn’t be questioned.

Landis felt the same way about the Pirates owner. “When I think of Barney Dreyfuss, I think of integrity, fidelity — of Gibraltar,” he said.

Landis was the commissioner during Pittsburgh’s last run of greatness under Dreyfuss’ ownership. The 1925 team, with future Hall of Famers Max Carey, Kiki Cuyler and Pie Traynor, won the World Series in seven games over the Washington Senators.

Dreyfuss eventually sought to step back from the game, handing over control of the team to his son, Sam, in 1930. Tragically, Sam died one year later of pneumonia.

The tributes poured in when Dreyfuss died on Feb. 5, 1932, also after suffering from pneumonia.

“He was first and always a sportsman of the highest class,” said Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert.

“He was a real fan and one of sportsdom’s leader,” said American League president William Harridge.

In the eulogy delivered at Rodef Shalom Temple, prior to burial at West View Cemetery, Dr. Samuel Goldenson said, “Here was a man who elevated a mere sport to the dignity of an honorable and magnificent business. … It is fair play we have most need of in the world, and this man made it the object of his life.”

While Dreyfuss was revered in his time, it took more than seven decades before he received his proper recognition in Cooperstown. Finally, on Dec. 3, 2007, the Veterans Committee gave him a spot in the Hall of Fame.

“The Pirates are extremely thrilled that Barney Dreyfuss was elected,” team president Frank Coonelly said of the news. “Mr. Dreyfuss was a dynamic, innovative and extraordinarily competitive owner who built the Pirates into the dominant National League club at the turn of the century.”

On a Sunday afternoon the following July, Andrew Dreyfuss accepted on behalf of his great-grandfather. Andrew ended his speech with a story that said much about the new Hall of Famer.

“I’ll close with a story that illustrated our great-grandfather’s generosity and dedication to baseball,” Andrew said. “In the 1920s, Pittsburgh had a minor league team, the Comers, in Columbia, S.C. In 1926, Columbia’s wooden stadium burned to the ground and the city did not have the resources to build a new one.

“Barney Dreyfuss was so passionate about baseball that he donated the necessary funds to build a new stadium. Columbia’s Dreyfuss Field opened for play in 1927 and has housed minor league and college baseball teams for (more than 8 decades).”

Now that’s quite a legacy.