“G-d works in mysterious ways”: Former pitcher Bob Tufts on lessons learned from conversion to Judaism and baseball

There is much more to Bob Tuft’s story than what he did in the big leagues.

There is much more to Bob Tuft’s story than what he did in the big leagues.

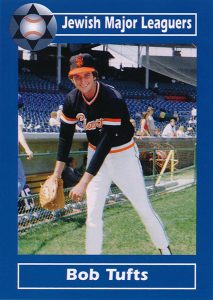

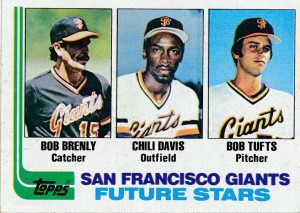

A 6’5” left-hander with good breaking stuff and, by his own admission, “a really bad-looking motion,” Tufts was drafted by the San Francisco Giants out of Princeton University in 1977. He went on to spend parts of three seasons in the majors as a reliever for the Giants and — after they traded him to Kansas City with Vida Blue in the deal that sent future All-Star Atlee Hammaker and three other players to San Francisco — the Royals, posting a 2-0 record with two saves and a 4.71 ERA in 27 major league appearances. Arm troubles forced him to retire from the game at the age of 27, following the 1983 season.

But the most notable thing about Tufts’ MLB career didn’t happen on the diamond; rather, he’s one of just a handful of major leaguers to convert to Judaism during his playing career. Tufts began the process in 1980, and officially converted in 1982, the year he married Suzanne Israel, his college sweetheart. (Their daughter, Abigail, would go on to win silver medals in 2005 and 2007 as a member of the USA Maccabi Women’s Indoor Volleyball Team.)

Tufts earned a bachelor’s degree in economics at Princeton; after retiring from baseball, he earned his MBA from Columbia University. After spending 22 years on Wall Street with Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers and other banks, he now teaches business classes as an adjunct professor at NYU and Yeshiva University. Diagnosed with multiple myeloma in 2009, Tufts is now in full remission, thanks in part to aggressive and experimental cancer treatments; the experience led him to co-found an online not-for-profit called My Life Is Worth It, which advocates for patient and doctor access and choice in care.

Here is Tuft’s player page on JBM. And our Q/A.

*****

Short Takes

On developing as a pitcher: “In high school, I threw straight over the top and tried to throw as hard as I could; I had no idea where the ball was going. Eventually, it got into my mind that, gee, throwing the ball over the plate with movement trumps throwing as hard as you can and walking people regularly.”

On converting to Judaism: “I started questioning the idea that you can say or do everything bad as long as you say ‘Sorry’ at the end. That’s not how one should live one’s life. One should basically be focused on the here and now, as opposed to promises thereafter.”

On the similarities between athletics and academics: “Those that come prepared — who do read the assignments or work out or prepare — are the ones that succeed in class or on the field.”

*****

The JBM Q/A

You began your conversion process while you were in the minor leagues. You were raised in the United Church of Christ — why did you decide to convert?

My mom had gone away from the church — she decided once we went to college to go to a more Biblical-based one. The church had became more about being a social justice warrior, and it was not trying to use religion as an intellectual way to understand life, to make your life easier, how to deal with problems, how to cope with issues that you face, etc. It offered politically correct slogans and no substance, which does happen on both sides of the religious debate, as I have found out in shuls in Forest Hills.

I started questioning things back then in the late 60s and early 70s. And then, when you go to college, the first thing that happens is the evangelicals try to get you and try to proselytize, and it was basically about the trinity and not about having a personal relationship with G-d. If we’re made in G-d’s image, why can’t we have a personal relationship, and have our prayers go directly to G-d? And it was kind of like — click — that was the first point that really changed for me.

Then, it was about the personal responsibility quotient. I’d grown up in a town where there were basically very few Jewish kids; I started interacting more with Jewish kids once I got to Princeton, and I started questioning the idea that you can say or do everything bad as long as you say “Sorry” at the end. That’s not how one should live one’s life. One should basically be focused on the here and now, as opposed to promises thereafter. So another tumbler clicked. It’s like Elliott Maddox has written, “I chose to give my beliefs a name — and the name is Judaism.”

Most of your minor league teammates were supportive of your conversion, with the notable exception of Gene Pentz.

Sitting in bullpen in Tucson, Gene out of nowhere turned to me and asked me if I accepted Jesus Christ as my Lord and savior. I said, “Funny you said that, because I am converting to Judaism.” His response: “Well, you’re just going to Hell.” And then he turned back to watch the game. Shortly thereafter, he fared poorly as closer, as did another pitcher. I got the job, got hot, and when the [1981] strike ended I got called up to the Giants. G-d works in mysterious ways.

Is it true you told the rabbi that you wanted to take Sandy Koufax as your Jewish name?

Yeah, we were in Charlottesville, Virginia; the head of the Hillel was the rabbi with whom I’d gone through the conversion process, and we’d had our little bet din about the conversion. You choose a name that’s meaningful to you, and has meaning within the Jewish faith. So I said, “Sandy Koufax!” The three of them all laughed, but then I was like, “Okay, believe it or not, I actually have thought about it; I’m going to take Reuven, from Reuven Malter in The Chosen. Number one, because of the choice of religion; number two, because there’s a baseball component; and number three, it’s trying to wrestle with the issues of being religious within a secular society.”

What initially drew you to baseball?

What initially drew you to baseball?

My father, Bill, ran track, played football and was a very good basketball player. But he had some minor vision problems in one of his eyes, so he couldn’t play baseball. But my brother Bill was an all-state pitcher in high school. I was three years behind him in school; by the time I got to high school I was kind of a known quantity — I’d basically tagged along and played against kids older than me. I was forced to get better, or basically have a very thick ego and not get trashed about getting my head kicked in on a regular basis. [Laughs]

Did you idolize any particular pitchers while you were growing up?

I always liked Bill Monbouquette — but part of that was because after my mom, Barbara, graduated from college, she taught in Medford, Massachusetts, and she had Bill Monbouquette in her first class. But for people I really modeled myself after? There wasn’t anyone, really. Once I got to college, being a Red Sox fan, I did like the eccentricity of Bill Lee — but I did not exactly want to pitch like Bill Lee!

Were you more of a power pitcher?

In high school, I threw straight over the top and tried to throw as hard as I could; I had no idea where the ball was going. Eventually, it got into my mind that, gee, throwing the ball over the plate with movement trumps throwing as hard as you can and walking people regularly. [Laughs] By the time I went to college, I’d dropped my arm angle slightly and was throwing sinkers and sliders. I was basically like a lefty Roger McDowell.

Did any coaches at Princeton help you with that transition?

No, I did it on my own. I had a really bad-looking motion, and a very quirky one to begin with; no one wanted to mess with it, and no one could coach it. Through my entire career, very few people who were able to look at me and help me. The worst time I had in baseball — other than at the end, when I did have an arm injury, but I didn’t know about it — was in 1980, when I was playing in Phoenix, Triple-A for the Giants. I was just getting shelled, and I had no idea why. The trainer for the team, who had seen me play for parts of the two years before, saw that I was opening up my right shoulder too quickly. I adjusted and basically got my game and rhythm back, and avoided getting released in 1980.

On September 12, 1982, you won your first major league game, throwing two scoreless relief innings against the Twins in a game the Royals eventually won 18-7. Two days later, you recorded your first major league save, setting down 10 straight Mariners in a 5-2 Royals victory. What stands out in your mind from those two games?

Number one is something that was more interesting to Terry Felton, who was the losing pitcher that day. It was the sixteenth straight loss to start his and the final decision — he ended up going 0-and-16. My first major league win was his sixteenth consecutive loss!

As for the next one — when I was with the Giants, my parents had flown out to San Francisco [to see me play]; but I was a reliever, and I didn’t pitch at all during the series that they were out there for. But they showed up to this game and got to the ballpark right before the game started, and my mother and father and Suzanne, my wife-to-be, all got to see me pitch and get the save that day. So that was a very special one for me, because that was the only time they got to see me play in the major leagues.

As for the next one — when I was with the Giants, my parents had flown out to San Francisco [to see me play]; but I was a reliever, and I didn’t pitch at all during the series that they were out there for. But they showed up to this game and got to the ballpark right before the game started, and my mother and father and Suzanne, my wife-to-be, all got to see me pitch and get the save that day. So that was a very special one for me, because that was the only time they got to see me play in the major leagues.

1983 was your last year in the majors. Was that because of the undiagnosed arm injury?

Yeah. I basically couldn’t get anything on my pitches, and I didn’t know why. I wasn’t experiencing any pain — every once in awhile there’d be some minor numbness in my hand, but it was like, “Gee, maybe I’m just getting old!” I didn’t find out until many years later that I basically had a torn labrum and a torn rotator cuff, and my capsule was slightly detached, and I had a few pounds of calcium deposits floating around in there. I was either very stupid or had a high pain threshold — I think I was probably guilty of both! [Laughs]

You were diagnosed with multiple myeloma in 2009. Were there any lessons you took from baseball or Judaism that helped you through the treatment and recovery process?

It was numbers and faith. The numbers side of the equation was, “Okay, I’m going to go in every week, and you’re going to evaluate what my protein levels are, and what these ratios are, to determine whether my health has improved, stayed the same or gotten worse.” My cancer was pretty high risk — so if the first treatment hadn’t worked, I probably would have been dead in a year. But it worked within a month, I had the transplant, and I’m cancer-free now.

And the other side is faith. Living in Forest Hills, Queens, you’ve got people from 178 different countries around the world, and you’ve got every different faith possible. I know they were all praying for me. I don’t know what the one true faith is, but someone out there had the right one, and their prayers for me probably helped me move down the line. Faith in individuals, faith that there’s some purpose involved in all this. Not that I got cancer for punishment, or to test my mettle. Basically, bad things happen to good people, good things happen to bad people; you just have to learn to deal with them.

Similarly, were there any lessons from your baseball experience that you’ve been able to apply to your teaching at NYU and Yeshiva?

The biggest lesson I took from sports to my current profession is that teaching can be a lot like coaching. In both cases, you cannot assume a “one size fits all” approach to maximize results. Coaches that use a “my way or the highway” approach do a disservice to their players by not treating them as individuals. Athletes have different skill sets and respond differently to instruction; sometimes, a player may just not “get it” when told what to do in the standard method.

In academics, people learn in different ways, so I try to offer verbal and written opportunities for students to express their understanding of the materials covered in the course. I use lectures, cases, presentations and traditional written homework assignments. Sometimes I even advise students to not use their computer and take notes by hand, to see if the tactile process of writing enhances retention. It also makes students rewrite the notes on the computer and discover whether they really understood the topic.

And from the perspective of the student or the athlete: Those that come prepared — who do read the assignments or work out or prepare — are the ones that succeed in class or on the field.

Dan Epstein is an award-winning journalist who has written about baseball, music and pop culture for Rolling Stone, Fox Sports, the Jewish Daily Forward and many other publications. His latest book, the acclaimed Stars and Strikes: Baseball and America in the Bicentennial Summer of ’76, is now out in paperback via St. Martin’s Griffin. His website iswww.bighairplasticgrass.com; you can follow him on Twitter at @bighairplasgras