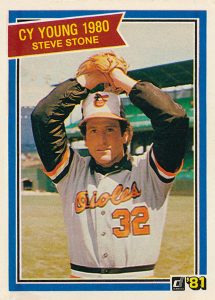

Q/A with Steve Stone: A most interesting life in baseball; why No. 32 meant so much to him

First of two parts

First of two parts

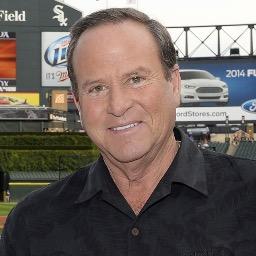

When it comes to lifetimes in baseball, Steve Stone’s ranks right up among the best, and definitely, most interesting.

As a player, Stone played with Hall of Famers Willie Mays and Jim Palmer, and played for Bill Veeck and Earl Weaver. As a broadcaster, he worked with all-time personalities in Harry Caray, Howard Cosell and Ken Harrelson.

Stone went 107-93 during an 11-year career. He saved the best for last in winning the 1980 Cy Young Award with a 25-7 mark with Baltimore.

When an ailing arm abruptly put an end to his playing days in 1982, Stone began a second career as a broadcaster. He quickly became one of the best analysts in the business while working both sides of town in Chicago.

There were so many stories and insights during our long JBM interview, we decided to break it up into two parts. In part 2, Stone will share numerous entertaining tales about his encounters with the greats of the game.

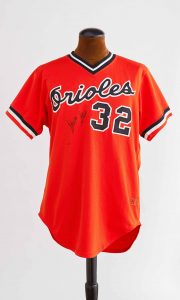

In part 1, Stone reflects on his long career. Like most Jewish kids of his generation, the Cleveland native explains why N0. 32 always will have special meaning to him.

Did you ever get to meet Sandy Koufax?

No, but I talked with him when we did the painting of the Jewish Major Leaguers. It gave me a chance to connect with him.

I was told you were instrumental in convincing him to do the project.

He said he wouldn’t have done it if not for me.

What was it like to pick up the phone and hear that Sandy Koufax was on the other end?

What was it like to pick up the phone and hear that Sandy Koufax was on the other end?

Wonderful. He was terrific. I said, “I’m just happy to get a chance to speak with you, and my real disappointment was never really having the opportunity to spend any time with you.” I told him, “If you don’t know it, I won the Cy Young award wearing 32, and every chance I got, I wore No. 32.”

Yes, you did. I never put that together.

In fact, they gave me 29 when I first got to Baltimore. Joe Kerrigan, a guy who later became a pitching coach in the Major Leagues, wore 32. As long as Kerrigan was around, I wasn’t going to ask him for his number. When he got let go, my 29 became 32 again.

I wore 32 with the White Sox. The Cubs gave me 30 because I think (legendary Cubs equipment man Yosh Kawano) gave all the Jews No. 30. He gave Kenny Holtzman 30 before me, so I think he thought 30 was the Jewish number.

When I had the choice, I always picked 32.

And you told that to Koufax. That must have meant something for him to hear that you won the Cy Young wearing his number.

I know it meant a lot to me.

The High Holidays are coming up. As a player, did you follow Koufax’s lead and not play on those days?

I don’t work on the High Holidays and never have. Sandy is my hero and Sandy never performed on the High Holidays, and in fact it was the great World Series moment that he didn’t pitch in which got all that acclaim. But Sandy didn’t do it for the acclaim. Sandy did it because that’s what he believed in. It was a show of respect for Sandy. I didn’t necessarily do it because Sandy did it. If I didn’t believe in it, I wouldn’t do it regardless of what Sandy did. But the fact that he was my hero and the fact that there was never any scandal attached to his name off the field, he conducted himself exceptionally well as a professional player, well, if you’re going to make a choice on who to emulate, I’m thinking Sandy Koufax was a pretty good one for me.

You continue to refrain from working on the High Holidays as a broadcaster.

It’s not necessarily because of my religious beliefs, but it is out of respect for my grandparents and what they went through to get to this country. My grandmother came from a family of 13 kids in Russia, and 10 never made it out. Three made it to relative safety, one in South America and two in Ohio. My grandmother, being one, and her sister being another. When I look at the history of my ancestors and my direct family, knowing that my four grandparents all came from the old country, my mother’s father was Hungarian, her mother was Polish‑Czech, and on my father’s side, my two grandparents are Russian. So they all fled the old country and came and made a new life here. It was the persecution and everything else that historically the Jews have gone through. I do it out of respect for not only my family but the family of all the Jewish people who went through certainly a lot more than I did trying to make a life for myself in this country. It was certainly relatively easy for me, very difficult for them.

It’s more a show of respect for those who have come before me.

You came from a family of baseball fans.

My grandfather became a huge baseball fan well before I was born. He loved the game, and the family were very big fans of the Cleveland Indians.

I come about my athletic ability from my mother and the love of the game from my mother’s side of the family. My dad also loved baseball. But yeah, we were a baseball family.

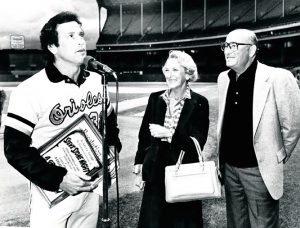

Stone with his parents being honored in his hometown of Cleveland before a game.

Your mother attended an Indians game the night before you were born.

Her father asked her what she was doing, and she said she was going to the game. He said, “Are you worried?” She said, “No, if I give birth at the game, Bill Veeck will give me free tickets for the rest of my life.”

Despite being an eventual Cy Young Award winner, you were not start a star pitcher in Little League. You were a late bloomer.

I was small, and I didn’t really have much of a fastball. So it took a while. And then starting with my junior year, I grew two and a half inches and 30 pounds, and I started to have a fastball. From the age of 16 to the age of 23, I just kept throwing harder with every succeeding year. That propelled me into the Major Leagues.

When you made your Big League debut with the Giants in 1971, you joined a team that had four future Hall of Famers: Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, Juan Marichal and Gaylord Perry. What was that like?

Yeah, a pretty good list of players, along with Bobby Bonds, who was a member of the 30/30 club five different times with five different teams. We had a pretty good team. Being in the Major Leagues and looking around and seeing four of the all‑time greats was pretty awe‑inspiring.

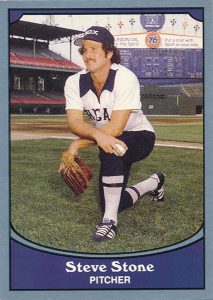

Eventually you ended up in Chicago, going back and forth between the White Sox and Cubs. That’s where your career started to blossom.

Eventually you ended up in Chicago, going back and forth between the White Sox and Cubs. That’s where your career started to blossom.

Rick Reuschel and I in ’75 led the Cubs’ staff in winning percentage. I was 12‑8 that year. You know, I was pretty good. Then I got hurt the next year, had a rotator cuff problem in ’76. The White Sox gave me an opportunity in 1977, and I won 15 games. “The South Side Hit Men” were very good in ’77. I was the No. 1 guy in ’78, also, won 12 games, .500 pitcher for a team well under .500. Yeah, those two were nice years.

After 1979, I moved on to Baltimore where all the really great things happened.

You went 25-7 in 1980, retire 9 straight batters as the American League starter in the All-Star Game and win the Cy Young Award. What did it mean to you to kind of have that year at that point in your career? Was there a sense of validation?

(Note: In July, we detailed Stone’s big year and All-Star game start.)

Well, I knew that I wasn’t great. I knew that I was just borrowing greatness for a short period of time, and eventually it would go away. So I tried to enjoy each and every moment of it. Vindication probably is the more appropriate word. I felt during the middle of 1979, there was a better pitcher inside of me and that I hadn’t been able to get it out yet. I didn’t know for sure, I just thought that there was. And I started on a path to be able to get out of myself everything that I could, and it worked. It was amazing. And from the middle of 1979 until the end of 1980, I went to the mound 50 times, 50 starts, in a year and two and a half months. I made 50 starts. I lost seven times.

Well, I knew that I wasn’t great. I knew that I was just borrowing greatness for a short period of time, and eventually it would go away. So I tried to enjoy each and every moment of it. Vindication probably is the more appropriate word. I felt during the middle of 1979, there was a better pitcher inside of me and that I hadn’t been able to get it out yet. I didn’t know for sure, I just thought that there was. And I started on a path to be able to get out of myself everything that I could, and it worked. It was amazing. And from the middle of 1979 until the end of 1980, I went to the mound 50 times, 50 starts, in a year and two and a half months. I made 50 starts. I lost seven times.

You became the answer to a trivia question: Who is the other Jewish pitcher to win the Cy Young Award besides Sandy Koufax?

I describe it as one was great and the other was me.

Unfortunately after 1980, injuries quickly ended your career. When did you start experiencing pain in 1981?

I was hurting in Spring Training that year. My arm just never came back from 1980. I didn’t throw the 251 innings in the middle of my career. I threw it, as it turned out, toward the end of my career. Because I had thrown so many curveballs that year, I think it just kind of wore away my elbow, and I never was healthy after that season again, but it was all worth it. Every minute of it was worth it.

Was it hard to realize that it was over so quickly after you had this big successful year?

Well, it’s always hard. You know, you’re hoping that it would come back again, that my arm would feel good again. It just didn’t. And I promised myself two things: One, I would pitch as long as it was fun, and two, I would hope to have the good luck to be able to leave before they asked me to. And I was able to accomplish both. Because after taking a cortisone shot in my elbow, actually two of them, a week apart from one another, and then trying to pitch again and knowing that the pain wasn’t going to go away, that was it. Time to take it off, look for something else.

You went immediately into broadcasting. Did you pursue it or did ABC come after you?

They came after me. I was unemployed for four days. As soon as I announced my retirement, I walked out, and one of the Orioles’ secretaries came up to me, and her name was Helen, and she said to me, you got two calls. One was David Hartman. He wants you to be on Good Morning America with him. I said, yeah, “What’s the other?’ She said, “The other one I would call back first. It was Chuck Howard, the vice president of ABC Sports. He’s got a job for you.”

And so I called him back, and he asked me if I’d be interested. Keith Jackson was going on vacation, would I like to do a couple of games? I said, sure. Two months out of the game, it’s Steve who, and now this was my chance to show somebody that I could actually do something, which was the equivalent of being invited to Spring Training as a non‑roster player and making the team. I had a three‑game tryout. I’m still broadcasting. It’s 2017. I obviously made a few teams.

When you were playing, did you get a sense that Jewish fans were behind you, rooting for you?

No, I didn’t. I felt that until I won the Cy Young award, the Jewish community didn’t want to have a lot to do with me. I think they wanted their players to be Sandy Koufax, and anything less than greatness, you weren’t exactly embraced by the Jewish community.

In fact, I got very few invitations to speak at events and a number of other things involved with the Jewish community until I won the Cy Young award. Then when I won it, all of a sudden, people came out of the woodwork. I remember I had this discussion with a Cleveland rabbi, who didn’t get in touch with me until after I won the Cy Young award, despite the fact that I started playing pro ball in 1969. This was the winter of ’80, going into the ’81 baseball season.

I said, “Let me ask you a question. As a Jewish Major Leaguer, I was the member of a very small club. It doesn’t really grow with every passing year, just kind of stays stagnant, and in some cases, it actually gets a bit smaller. But here I am a Cleveland guy playing professional baseball since 1969, and just now you’re getting in touch with me?”

Well, he couldn’t really explain it except that he was hopping on the bandwagon.

You can pass for 40, but you just turned 70. Do you plan on being around for awhile in the booth?

I should hope so as long as I feel good. First of all, there’s a couple things that come into play, and it goes with the same thing I told myself as a player. I would stay around just as long as it was fun because life in the end is really too short. As you get wend your way around the aging process, you realize it’s a lot shorter. You see some of your friends going to the big ballpark in the sky.

But I feel the same way. Number one, most importantly, I truly love baseball and have as long as I can remember. I find it infinitely complex and yet rudimentary simple. It’s like chess. There’s 64 squares and you love the moves, you’ve got your pieces, your opponent has the same pieces, there’s no luck in chess. And it’s multi‑layered. You just have to peel back the layers of the onion, and chess can be as simple but as complex as you can make it, and baseball is the same way.

Baseball on its face is a very simple game, but you delve down into is it and it has complexities and layers, and to truly understand it there’s a lot of things that you have to look past, and the longer you’re around, the more you realize there is so much to know. You never can really fully harness it. There are guys who are much better at it than others but nobody really grasps the entire game because there’s so much to it.

That for me has been a lifelong love of the game of baseball, and there’s no better place to be able to evaluate it than in the Major Leagues, realizing that these guys, although they are the best players in the world at their sport, the best in the world are playing Major League Baseball, and yet they still make what would appear to be just simplistic mistakes. Well, why would that possibly be if these are the best players in the world, why are they still making mistakes? It gives you some insight of just how difficult this game played at its highest levels is to be able to master. And that’s why the greatest of the great belong in the Hall of Fame, and the others like me, just are happy to have been around this long.