Former PR man Marty Appel answers question: Were Yankees once anti-Semitic?; His memories as fan and working for team

Ron Blomberg was part of Marty Appel’s lifetime in baseball.

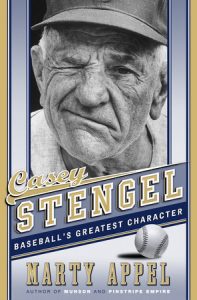

JewishBaseballMuseum.com is thrill to get this special contribution from Marty Appel. Appel, author of 24 books including the newly published biography Casey Stengel: Baseball’s Greatest Character, spent 20 years with the Yankees in PR and television production capacities and continues to contribute to their publications and website. He has also worked for MLB, WPIX TV, the Atlanta Olympic Committee, and the Topps Company, and heads his own public relations firm in New York.

In this piece, Appel shares some memories from a lifetime in baseball.

******

Appel working in his office today.

I was a first generation baseball fan, raised in mixed working class communities in Brooklyn and Queens, but more interested in connecting with the kids in the ‘hood whose common bond was baseball.

I was told that my religion was Jewish, but the afterschool trips to Hebrew School at the Maspeth Jewish Center, passing kids on playgrounds playing ball, was for me a pretty good indication that my true calling was on the playing fields of Maurice Park, not in the classroom learning to read Hebrew.

Still, I was an obedient and conscientious child, head of the AAA safety patrol in public school, and if my parents said I was going to Hebrew School, that was where I went. My trusty infielder’s mitt, a Billy Goodman model, (manufactured by Hutch) would rest quietly at home while I dealt with my studies. (Goodman was the A.L. batting champ in 1950 and a lifetime .300 hitter).

The mitt actually wasn’t trusty at all. Our gloves said a lot about our level of ability, and in fact, pretty much forecast our future. The better players in the neighborhood already had Spalding, Wilson or Rawlings gloves. Mine was just a step above Hasbro. Or maybe I should say a step above Aunt Jemima, because it looked like a pancake sitting there, unable to properly fold over when catching a ball. When coaches would yell “two hands, two hands,” they had these sorts of gloves, and kids like me, in mind.

Appel (left) with his brother in 1959.

I didn’t realize that I would have a long road ahead of me just to be “good,” but I did know the glove wasn’t helping. I also had a decent size fear of getting hit by a pitched ball, and it wasn’t until I mentioned this to the Yankees third baseman Graig Nettles, many years later, that he said, “…only hurts for a minute. By the time you’re at first base, the 60 seconds are almost gone.”

How come I never had a coach who told me this?

Anyway, I did begin to fall in love with other aspects of the game – the game’s off-field “culture,” so to speak. The cards, the literature, the broadcasts, the record book, the “Pride of the Yankees” movie – things like that.

I found myself a Yankees fan, quite by accident. I was seven. It was during the 1955 World Series when I was still living in Brooklyn, and the Yankees-Dodgers World Series led to the only Dodgers world championship ever won in that humble borough. I saw people literally dancing in the street from my Bed-Sty window, and instead of joining in the joy, the little boy that I was felt badly for the losers. I decided that very afternoon that I would embrace the underdogs, the Yankees, little realizing of course how foolish that would later sound. The Yankees had beaten the Dodgers head to head in their five previous World Series meetings.

So I had a little Yankees cap and I soon got a 1956 Yankees Yearbook, purchased by my mother at the corner candy store. She was a German refugee, and had little understanding of the Yankee history of being, um, less than enlightened, when it came to “minorities.” And of course, neither did I. All I would come to know was that Mickey Mantle was the hero, and in time I’d come to designate Bobby Shantz and Bobby Richardson as “favorite players,” perhaps became they were sort of my size.

The whole thing of the Yankees being slow to integrate and not especially known for their connection to New York’s Jewish community, went right past me. The Dodgers were the more “Jewish” team, with Jake Pitler coaching at first, Cal Abrams as an outfielder, and a kid from Lafayette High, Sandy Koufax, on their pitching staff. The Giants had recently had Sid Gordon in their infield.

But to us kids on the streets of New York, ethnicity of the players was not significant. We knew Jackie Robinson was the first “Negro” player – you heard that all the time….and that Joe DiMaggio was a hero to Italians, but did we really know or care what Mantle was? Or Duke Snider? Or Whitey Ford? They were defined by their teams and by their stats.

From time to time, sometimes at gatherings of the “cousin’s club,” my father’s generation – those who were baseball fans would call me out on supporting the “anti-Semitic” Yankees. This was news to me, but they wanted to talk baseball to me, because it was a subject we could find common ground on. “Lou Gehrig was in the Bund,” they would say. There was no such evidence that he was in this pro-German organization that cropped up in the late ‘30s. “Babe Ruth was an anti-Semite,” they would say. (There was no such evidence; Ruth signed an anti-Nazi ad in the New York Times during the war). The Yankees, to them, were somewhat of an object of scorn, never having had a Jewish player that anyone could remember. (Hymie Solomon, a Babe Ruth roommate, had become Jimmie Reese). Their audience seemed to be the “Wall Street crowd,” a somewhat derisive comment, particularly since many thought of that crowd as Jewish. It got a little confusing to me.

Since there were so few Jewish players anyway, so far as I could tell, it wasn’t as though other teams were stockpiling them. It wasn’t as though Barry Latman of the White Sox was the missing ingredient for the Yankees going to another World Series.

Of course, this is all my New York City experience. I cannot say other towns across America were the same. But for us street kids trading baseball cards, playing stickball, and watching games on TV, this was the reality. Could a player hit for average, hit with power, run, field and throw? This was the currency we dealt in.

I was in the Bobby Richardson Fan Club. Bobby was a lay minister in the Baptist Church, and a guest speaker at Billy Graham rallies. Our mailings included little religious tracts. I wasn’t offended. He was often identified as a religious guy. It seemed like this was what one would expect in such a mailing. We are friends to this day (he will be 82 this summer), we can discuss anything, and he knows I’m past the point of being saved. (His wife Betsy – I’m not so sure).

It was my good fortune that a letter I wrote to Yankee PR man Bob Fishel in the summer of 1967 resulted in my being hired to answer Mickey Mantle’s fan mail. The Mick was no longer carting these boxes of letters home to slave over them at night. (I believe he stopped doing that in 1952). Fishel knew the letters needed responses, so for $100 a week, I was brought aboard on the strength of my letter. Not many college students were looking for summer employment with the Yankees during the Summer of Love.

This was the first time I ever heard outward expressions from people of “What? The Yankees hired a Jewish guy?”

Maybe my universe had expanded with the college experience, although I was at a public college in the middle of New York State, and I still remember the name of a Republican student there. But there was some surprise that the Yankees had made this gesture.

Old Yankee management might not have extended themselves to me. Fishel was a non-practicing Jew, who went back to the regime led by Dan Topping and Del Webb. Before them came the Jacob Ruppert years in which Ed Barrow served as general manager. George Weiss, Barrow’s successor, was thought by some to be Jewish because of his last name, but he was not. You could not, in fact, find a Jewish name anywhere in the front office, although in those days, the front office was perhaps 35 people.

Weiss hired Fishel, (formerly with the St. Louis Browns), and knew he was Jewish, and he also knew that most of the writers who covered the Yankees were Jewish and thought that it could be a good thing. (Mel Allen, the legendary team broadcaster, was Jewish as well, which was a surprise to most people).

Appel working with the Yankees in 1970.

By the time I was hired, a much more enlightened management had moved in. Michael Burke, designated by CBS ownership to run the team, brought a new management style to the corporate culture. He convinced Lee MacPhail, our general manager, to make Ron Blomberg the nation’s number one draft selection in 1967. He brought in Howard Berk as his right hand man in the front office. He had National Urban League director Whitney Young throw out a first pitch on Opening Day. He opened Yankee Stadium to the Newport Jazz Festival.

And when it was time to select an assistant to Fishel in the PR Department, Bob’s Irish-Catholic assistant having moved on, the job went to me. Fishel had liked my work (it came to extend far more than answering fan mail) and Burke approved. In this particular administration, it was not an issue.

Appel’s new book on Casey Stengel.

George Steinbrenner, who followed Burke, inherited a now-liberated organization. Steinbrenner had his detractors and could be cruel and dictatorial, but being anti-Black or anti-Jewish was not among his flaws. His hiring record proved that, and in the hundreds of private meetings I had with him over the years (I was by 1974 Fishel’s successor as PR Director), he said a lot of things I would never repeat, but he never anything that diminished another person because of race or religion.

His open attitude did not necessarily reflect the signing of Jewish players. After Blomberg came Ken Holtzman and the converted Elliott Maddox (unknown at the time he was a Yankee), and eyebrows were raised when manager Billy Martin bypassed the rested Holtzman to open the 1976 World Series, opting for reliever Doyle Alexander. Then, there were no Jewish Yankee players until Kevin Youkilis in 2013 and pitcher Rich Bleier in 2016. This was during a so-called “golden era” of Jewish major leaguers when as many as a dozen or so appeared each year on major league rosters.

(The only true “golden eras” of course, were when Hank Greenberg played and when Sandy Koufax played, and they didn’t need Jewish contemporaries to make the era light up).

So were the Yankees an “anti-Semitic” organization?

Historically, perhaps. Certainly not by the time I joined them 50 seasons ago, and I never had that conversation with the holdovers from the Topping-Webb days. (There were no Ruppert-Barrow holdovers). And I would say that it was not the case during the Steinbrenner era, suggestions about various anti-Semitic players or manager aside. Those feelings did not carry over to the front office, the broadcast booth, to vendors, or to hirings. In fact, the team President today is Randy Levine, and the Chief Operating Officer is Lonn Trost, both Steinbrenner hires and both Jewish.

It’s not my father’s Yankee organization anymore.