Jews in the press box: Biggest names, innovators shape reporting on baseball

Shirley Povich

In 1954, New York Yankees general manager George Weiss found himself with a position to fill when public-relations director Red Patterson left to work for the crosstown Brooklyn Dodgers.

Weiss, who was not Jewish, landed Bob Fishel, who’d held the position for the St. Louis Browns. Fishel was plenty qualified, but Weiss had another motivation.

“Weiss said he hired Fishel because he was Jewish and so many of the writers were Jewish,” said Marty Appel, who would know, having later been hired by Fishel to work in the Yankees’ public-relations department. The ethnic connection, Weiss apparently figured, would be to the team’s advantage.

Indeed, the era featured prominent New York-based baseball reporters who were Jewish. They included Dan Daniel (who’d started covering baseball more than 40 years before), Harold Rosenthal, Joseph Reichler, the brothers Milton and Arthur Richman, Barney Kremenko, Milton Gross and Dick Young. In Washington, there was Shirley Povich; in Chicago, Jerome Holtzman; in Ohio, Si Burick and Hal Lebovitz.

Then came men like Maury Allen, Ira Berkow, Murray Chass, Jerry Izenberg, Vic Ziegel, Moss Klein, Hal Bock, Leonard Koppett, Leonard Schecter, Ross Newhan, Robert Lipsyte and many, many more.

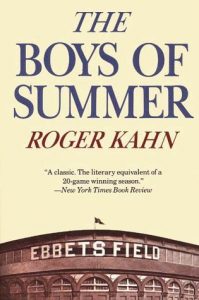

Other Jewish scribes made a greater mark by writing books – some of them classics – on baseball, including Zander Hollander, Lawrence Ritter, Donald Honig, Roger Kahn, Ray Robinson and Arnold Hano.

And of course, one of baseball history’s most beloved broadcasters was the Yankees’ Mel Allen.

Jerome Holtzman

Allen, in fact, received the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum’s lifetime award. So did Daniel, Reichler, Milt Richman, Young, Holtzman, Povich, Burick, Lebovitz, Chass, Koppett and Newhan.

The Cooperstown institution’s president, Jeff Idelson, is a Jewish American who once worked for the Yankees, as is the case with Appel and with the late Allen and Fishel.

“Baseball as a sport has long been a leader in inclusiveness,” Idelson said. “The fact that many Jewish journalists cover the sport as writers and broadcasters is an extension of that inclusiveness. Very generally speaking, people of Jewish faith tend to have a strong intellectual curiosity, and that’s reflected in the large number of Jewish journalists who have been honored with the [Hall of Fame’s] J.G. Taylor Spink Award.”

Today, the Jewish roster of journalists and broadcasters covering baseball, and covering it well, is much longer.

“You have to start with the [saying] about Jews being the People of the Book. Reading and writing have always been important,” Berkow explained. “Especially with baseball, to be an American was to know baseball, as an aspect of assimilation.”

It was Povich, in his October 8, 1956, column in The Washington Post, who composed one of baseball journalism’s most memorable article “ledes,” or openings.

“The million-to-one shot came in. Hell froze over. A month of Sundays hit the calendar. Don Larsen today pitched a no-hit, no-run, no-man-reach-first game in a World Series,” Povich’s report began.

The son of immigrants from Lithuania, Povich wrote and edited for the newspaper for an astounding 75 years, spanning Walter Johnson to the day before Povich died in 1998 at age 92. His legacy extends beyond the Post’s newsroom, to the University of Maryland’s Shirley Povich Center for Sports Journalism and to the Washington Nationals’ press box that is named in his memory. The press box’s entrance displays Povich’s fedora, pins from the scores of World Series he covered and his scorecard from the Larsen game.

Among Povich’s many admirers was Tony Kornheiser, a Post sports writing colleague (and also Jewish) and now a broadcaster.

“He kept one eye on the past for the sake of perspective, but he always had both feet in the present,” Kornheiser wrote in a 2005 book about Povich. “He could tell you about Calvin Coolidge, who was the president of the United States when Shirley began writing at The Washington Post, and he could tell about Calvin Ripken.”

Appel, who after leaving the Yankees crafted a successful career in public relations that includes many baseball clients, said that Chass’s work beginning in the 1960s and ’70s “kind of changed the face of sports journalism.”

“He led the movement of not running teams’ press releases, and finding his own stories,” Appel said of Chass, who came to the N.Y. Times from the Associated Press.

“Chass led the rebellion and said, ‘No, thank you, we’ll decide what the news is,’ ” Appel said.

A sea change also occurred about then in baseball literature, when Kahn, who had covered the Brooklyn Dodgers for the N.Y. Herald Tribune, published “The Boys of Summer.”

A sea change also occurred about then in baseball literature, when Kahn, who had covered the Brooklyn Dodgers for the N.Y. Herald Tribune, published “The Boys of Summer.”

In the 1971 book, Kahn visited former Dodgers players two decades following their heyday, after fans’ cheers had faded and middle-life challenges set in.

The work represented a “major transition” in baseball writing from what had been the romanticizing of athletes on the field, said Rabbi Mayer Schiller, whose first baseball love was the Philadelphia Phillies of the late 1950s.

Kahn’s description of coming to see former rightfielder Carl Furillo at his construction job, and third baseman-turned-bartender Billy Cox, “accepts the tragic and realistic, but is not devoid of enchantment,” said Schiller, a Skver Hasid who teaches Talmud in one New York school and English literature in another.

He added: “It’s like [Yiddish author] Sholem Aleichem. He’s not happy with every aspect of the shtetl he writes about in his books. He looks at it in its totality. He has great affection for all the characters, although he’s not blind to their warts. It’s the idea that one can write realistically, but affectionately.”

Honig, who continues writing baseball books at age 84, finds that discerning a distinctly Jewish voice in these writers’ work would be challenging, though.

“If you read all these guys without a byline, I don’t know whether you could identify any of them as being Jewish,” Honig said from his home in Connecticut.

Twenty minutes later, Honig bade a telephone interviewer goodbye with the Yiddish, “Zei gezunt!”