Q/A with Norm Sherry: How he fixed Sandy Koufax and once managed Kurt Russell

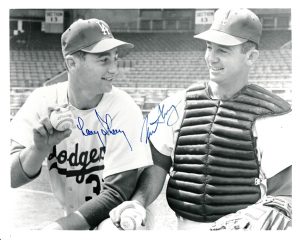

With brother, Larry.

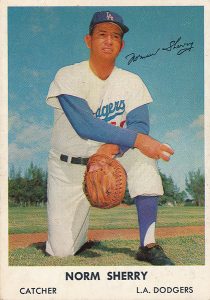

Norm Sherry has a special place in baseball history. The former Dodgers catcher will be forever known as the person who straightened out Sandy Koufax, transforming him into the best pitcher the game has ever seen.

Sherry and his brothers fell in love with baseball, playing and earning some change with their Los Angeles neighborhood’s minor-league team, the Hollywood Stars. He became a catcher for the strong Dodgers teams beginning in the late 1950s and finished his short career with the atrocious Mets in 1963.

During all of Sherry’s Dodgers years, a teammate was younger brother Larry, a standout relief pitcher. Norm then embarked on a three-decade career as a scout, coach and manager in both the minors and majors. Besides Koufax, he also worked with the wondrous Nolan Ryan.

Later, Sherry tutored a young catcher named Gary Carter, setting him – as he had Koufax – on the path to Cooperstown. In the minors, he managed the team owner’s son, a second baseman who would become famous off the field: actor Kurt Russell.

How good was Sherry? Hall of Fame manager Dick Williams brought him on-staff for three teams, with one reaching the World Series. Now 84, Sherry possesses a wonderful sense of humor and retains keen memories of his baseball career.

Here is our JBM Q/A:

*****

Short Takes

* * *

As kids watching high school players’ wayward throws land in the bushes, “we marked them, and when they were done practicing and left the field, we’d run and get ’em. So we said, ‘Let’s play like they did.’ We got the bug to play baseball.”

Larry the pitcher to his brother the catcher: “Thanks, Norm, you saved my ass. You saved my career.”

“[Dodgers teammates] called Koufax the Super Jew, because who was as good as him? Nobody. Larry, they’d call the Rude Jew, because he was mean out there. They called me the Jolly Jew because I had a good disposition and didn’t get upset.”

In 1961 spring training, Sherry advised a wild Koufax, “Why don’t you take something off the ball and just put it in there? Don’t try to throw it so hard. Just put it in there and let them hit it.” By inning’s end, Koufax had struck out the side, and Sherry told him, “Sandy, I don’t know if you realize it, but you just now threw harder than when you were trying to.”

*****

The JBM Interview

The JBM Interview

I know that you played a big role in turning around Koufax’s career. What do you remember about that?

A: It was 1961 in Orlando, where we went to play the Twins in an exhibition game. We’d talked on the plane going over there, and he said, “I want to work on my change-up and my curveball.” We went with a very minimal squad because one of our pitchers missed the plane. Gil Hodges went as our manager. [Koufax] couldn’t throw a strike, and he ended up walking the first three guys. I went to the mound and said, “Sandy, we don’t have many guys here; we’re going to be here a long day. Why don’t you take something off the ball and just put it in there? Don’t try to throw it so hard. Just put it in there and let them hit it.”

I went back behind the plate. Good God! He tried to ease up, and he was throwing harder than when he tried to. We came off the field, and I said, “Sandy, I don’t know if you realize it, but you just now threw harder than when you were trying to.” What he did was that he got his rhythm better and the ball jumped out of his hand and exploded at the plate. He struck out the side. It made sense to him that when you try to overdo something, you do less. Just like guys who swing so hard, they can’t hit the ball. He got really good.

Your brother Larry also was on that Dodgers team. A reliever, he was the MVP of the 1959 World Series.

The [other players] called Koufax the Super Jew, because who was as good as him? Nobody. Larry, they’d call the Rude Jew, because he was mean out there. They called me the Jolly Jew because I had a good disposition and didn’t get upset. They all meant well. In the clubhouse, everyone was kidding one another. It was affectionate. They were all good fellas.

Besides catching Koufax, you coached and managed Nolan Ryan. That’s a heck of a unique combination. How did they strike you as pitchers?

Watching Koufax pitch was like watching a good artist paint. He just had a way with his delivery. Nolan – he grunted and groaned, but he threw hard, boy. Two different types of pitchers. Koufax was smoother and threw more consistent strikes to where he wanted. Ryan just reared back and threw it. You talk about guys and pitch counts – with the Angels, he’d be going into the ninth inning with close to 200 pitches sometimes.

I remember I left him in a game at Detroit, and John Wockenfuss was up at the plate. I was going to take him out of the game because it was the eighth inning, and he was at 170 pitches thrown already. I thought, “The last time he was in this situation, he pitched out of it, so I’m going to let him go.” Well, Wockenfuss hit a homerun.

Last time we spoke, you were telling me about Moshe, the teacher in Hebrew school in Los Angeles.

Sherry: I was 9, George was 8, Larry was about 5. My brothers and I went from our regular grammar school, and on the way home we’d stop off at the corner of Fairfax and Melrose at an office building. Upstairs was a classroom where they’d teach Hebrew. We didn’t go very long, because this guy, Moshe – if you didn’t pronounce the words right, he’d take a ruler and swat you across the knuckles. We didn’t care for that, so we quit going and we didn’t go back.

We lived on Orange Grove Avenue, and a Rabbi Cohen lived next door to us. He might’ve been the one who said we should go to this Hebrew school. We went maybe two or three times to the classes. Our parents both were working. My father, Harry, was in the dry cleaning business. My mother, Mildred, was a milliner: She made women’s hats and dresses. My mother would be out of the house before we got up and she would come home from work at about 6:00 at night. Nobody said a word to us about not going [to Hebrew school].

How were you first drawn to baseball?

There were four of us boys. My mother was disappointed she didn’t have a girl. My older [half-]brother Stanley lived with my grandparents; my mother’s first husband had died of a brain aneurysm. We lived three houses from Fairfax High School. We’d see them playing baseball, and they used to throw over the first baseman’s head, and it’d go into these bushes, but there was a fence there, so [the players] wouldn’t go over the street. We marked them, and when they were done practicing and left the field, we’d run and get ’em. So we said, ‘Let’s play like they did.’ We got the bug to play baseball.

Come summertime, I’d get up early in the morning, get up all the kids on the block, and my brothers, and we’d go down and play on the girls’ field; you couldn’t play on the boys’ field, because they were getting it ready for football. We’d play a game called Over the Line. We’d have teams and we’d lob the ball to one another. The idea was that if you’d hit the ball on the ground between centerfield and third base, you’re out. If you hit the ball in the air and they didn’t catch it, you had a hit.

They had a fence out there and, I’ll never forget, I said, “One day, I’m gonna hit a ball over that fence.” I don’t know how many years later, but I finally did. That game Over the Line – I wish I’d never played, because I had that upper-cut swing. In fact, one year at spring training, Branch Rickey Jr. was there to look at all us guys in 1950. After I took batting practice, I came out of the cage and he called me over and asked me, “How long you been playing baseball?”

I said, “Since I was a kid.”

“And how many times did you swing that bat?”

“A thousand times, I guess. I don’t know!”

He said, “Let me tell you something: That’s how many times you swung it wrong” – and he walked away from me.

That upper-cut swing – that’s not the one you want. I got by with it in high school. When you get into professional ball, you’ve got a lot of guys who could throw it harder, and if you’re swinging up and they pitch you up and in, you’re not going to hit it. It took me a long time to hit correctly.

What do you remember about 1959: your first year in the majors, Larry’s a pitcher on the team and your Dodgers win the World Series?

In 1958, I had the best year I’ve had in minor league baseball. I went to spring training in 1959 and made the club, and played in Chicago in our first game. Got a base hit to drive in two runs and I was really happy. We got back to L.A., and they called me in to the office and said, “We’ve got to send you to Spokane.” So there I went, back to AAA. I never got back until the end of the season.

So were you on the World Series roster?

No, but I was there to help them. I saw my brother and said, “This is unreal.” I was so happy for my little brother (Larry was named the World Series MVP). I was warming up the pitchers. Then, I had to shower and I sat in the upper deck in Comiskey Park, next to Pete Reiser, down the rightfield line. Reiser’s wife, Pat, was Jewish. Her aunt was Fanny Hurst, the famous writer. I went to his funeral. He lived out in Palm Springs.

It must’ve been such a unique dynamic when you and Larry were in the game at the same time as the battery. What was it like for you?

I knew him and what he liked to do. That’s what you do as a catcher – try to work with that pitcher. When he’d shake me off, I’d have to go out and talk to him. One time, Smoky Burgess hit a single up the middle off Larry. I went out and said, “What the hell kind of pitch was that?” He said, “He hits everything I threw, so I wet my fingers and threw him a spitball.” I said, “You’ve got to be kidding me! You’ve never thrown one of those things in your life.”

It was fun to catch him. He was one of those pitchers who learned from his minor league manager that if your grandma came up to the plate, ol’ granny’s got to go down! He liked that. He threw a lot of up-and-in pitches at a lot of guys.

Which of Larry’s pitches did you like to call for?

His out pitch was a slider. He had a good fastball, slider and curveball. Usually, your slider’s going to be better than your curveball.

When you and Larry were teammates, you had the advantage of playing in your hometown, so did your parents attend many of the games?

My dad did, but my mom didn’t. She couldn’t stand watching. When I came up to hit, she’d walk away. It made her nervous.

Did she also get up and walk away when Larry was pitching?

Who knows? I’m her favorite – what the hell!

You enjoyed a long career as a coach. I’m wondering whether that started because of your insights into Larry’s pitching struggles.

You enjoyed a long career as a coach. I’m wondering whether that started because of your insights into Larry’s pitching struggles.

They say, “How can you be a pitching coach when you were a catcher?” Well, you’re looking at the pitcher throwing the ball to you all the time. Dodgers scout Kenny Myers taught us a lot about being a catcher, being a pitcher, all positions, and when I was watching the pitchers, it made sense to me what he was talking about. In those days, when you were a minor league manager, you didn’t have coaches; you did it all. I liked working with the pitchers. I did have that inner feeling of what a pitcher goes through.

I was a playing manager at Santa Barbara [the Dodgers’ A team] in 1965 to 1967. They said to me, “You’re not there to develop Norm Sherry!” It was a joke; I was already done playing.

Then, I scouted for the Yankees for one year, in Los Angeles, in 1968. I didn’t sign anybody. I saw one really good player: Tim Foli [a future major league shortstop]. In ’69, I scouted a little bit and managed a Rookie Pioneer League team for the California Angels, in Idaho Falls. Toward the end of that season, the Atlanta Braves wanted Hoyt Wilhelm, who was pitching for the Angels.

The Angels told me, “You’re playing their rookie team up there. Pick the best player off that team and tell us who it is and we’ll get them to trade him to us.” So I said, “Pick Mickey Rivers. He can run like a deer.” So Mick the Quick went to the Angels.

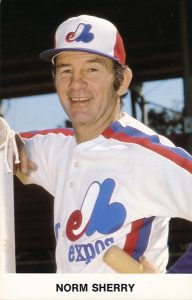

The next year, Lefty Phillips, who was my really good friend – he was one of the few Jewish people to become a manager – made me his pitching coach [with the Angels]. We all got fired after ’71. I stayed in the organization and managed AA ball: Shreveport, El Paso, Salt Lake City. Then I became the Angels’ third base coach in ’76. They fired Dick Williams in the middle of the season, and I managed through July of the next year. I did a little scouting for them, then I went on to Montreal – with Dick Williams again – in ’78 through ’81. Then [Williams and I] came to San Diego’82 to ’84. In ’85, they let me go as a pitching coach. In ’86, Roger Craig got the job [managing] with San Francisco and made me his pitching coach. I was there until ’91 – the last two years managing their rookie team up in Everett, Washington.

You were also with the Angels a long time.

Yeah, in El Paso, I had this kid, [Frank] Tanana. Man, was he good. He could bring the ball and he had great command. He was from Detroit, and he pitched for a league in high school, where if you threw three balls you walked the guy. So, he was used to throwing strikes. He was a really good pitcher.

It’s funny the things I remember. Also on that [El Paso] team, one owner of the ballclub, a AA team in 1973, was a guy named Bing Russell. He was a Western actor. He wanted his son to be on this team, too: Kurt Russell, the actor. He played second base for me. We got to El Paso, and I put him in the game because his dad was there. The son of a gun – he got about three hits. So I played him again the next night. He comes in after the first inning, I think, and said, “I can’t play. I can’t move my arm.” That was the end of his career with me. What a nice guy he was. The guys liked him. How he hurt his arm, I’ll never know.

What did you do to assist a young Gary Carter?

With Montreal, (manager Dick Williams) and general manager Charlie Fox called me and said, “We want you to come up here and be a coach. We’ve got this kid, and now he’s playing the outfield and catching some, but we want to make him just a catcher: Gary Carter.” That was my job. In spring training I was with Gary Carter all the time. I would tell him: “No, you don’t want your glove like that; you want it this way. … No, move your feet.” He must’ve gotten tired of me.

You did reach two World Series as a pitching coach with the 1984 Padres and the 1989 Giants, although your teams lost both. What was that like?

You’d like to do better – but if it doesn’t happen, it doesn’t happen. The most exciting thing is to get there. To be a World Series champ, that’s better yet; that’s gravy. It’s a good feeling, because all the guys you beat to get to that point – they’re watching, and you know what you’ve accomplished. You feel very proud of what you’ve gained by going that far.