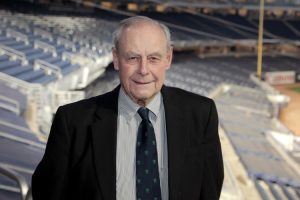

Sol Gittleman: Teaching baseball and America course at Tufts; author of Yankees book

A writer could hardly conjure a more enjoyable interview subject than Sol Gittleman. At 81, he exudes a youthful zest, with vivid memories of details and a strong, warm voice.

A writer could hardly conjure a more enjoyable interview subject than Sol Gittleman. At 81, he exudes a youthful zest, with vivid memories of details and a strong, warm voice.

A professor since 1964 at Tufts University’s School of Arts and Sciences, Gittleman has taught courses on German literature, Weimar culture, German silent films, the rise of Hitler, Yiddish culture, Sholem Aleichem, the Jewish-American novel and … baseball.

In 2007, he published his first book about the national pastime: “Reynolds, Raschi and Lopat: New York’s Big Three and the Great Yankee Dynasty of 1949-1953.”

* * *

Short Takes

Gittleman at 13: “I remember watching my first World Series game in ’47, going from bar to bar in West New York, N.J.”

“I created a “six-hit pool”: betting that kids couldn’t name three hitters who would get six hits together on any given day. … I made enough money for my first year of college!”

“Baseball’s not just baseball. It’s integration, immigration, law, transportation, travel, Manifest Destiny, race, labor and business relations, ethnicity, technology – a whole series of topics that really represents American history.”

* * *

The JBM Interview

How is it that you, a professor of Judaic Studies and of German, came to write a book in 2007 on three good-but-not-great pitchers – Allie Reynolds, Vic Raschi and Eddie Lopat – who played for the Yankees six decades ago?

Gittleman: As a young adult in 1949 – I was 15 years old – I was a passionate Yankees fan and a very dedicated baseball fan. I knew the rosters of all 16 teams and studied them. It became clear to me then that these three pitchers made this unique event take place – five consecutive world championships – and not the rest of the team. Without the three pitchers, nothing would have happened.

You could see that Mickey Mantle was a kid who broke water fountains, and that Joe DiMaggio was through. As I got older, I stopped rooting for the Yankees. Later in life, when I had the opportunity to teach baseball, I felt: “I don’t want to teach it unless I publish something.” So in 1993, I wrote this two-page article for the Society for American Baseball Research about these three pitchers. It caused me to have an itch I had to scratch. Fifteen years later, I wrote the book.

Did you interview Reynolds, Raschi and Lopat?

No, the first two were already dead, but I interviewed their living teammates, including Yogi Berra. They were very eager for me to write the book. Berra said, “Write the book. It’s important. Nobody knows about these three guys.” I talked to Eddie Lopat just before he died, then I spoke to his son and to family members of all of them. I was 70 when I started this [book]. It was part of my childhood. I used to deliberately walk like Eddie Lopat. He had a waddle. They’re forgotten now. The Yankee fans don’t know them.

It was the early years of Jackie Robinson, and I became interested in ethnicity in baseball and how the ethnic Americans dealt with the black Americans. The three guys: one was a Cree Indian [Reynolds], another was an Italian American [Raschi] and the third was a Polish American [Lopat]. Baseball is a rough game of cursing, big-mouth bigotry, prejudice, being called names.

What did it mean to you to metaphorically return to your childhood to research this book?

It meant that I wasn’t dribbling or drooling! I understood how the game had changed, how the ethnicity had changed. This was before free agency. These guys were slaves. The owners, at best, were paternalistic slave owners.

How did you come to be teaching the Tufts course on baseball and America?

The faculty member in the history department who was teaching sports in America, Gerald Gill, became terminally ill. A sweet, wonderful man, black, with diabetes; a beloved, great teacher. He asked me if I’d teach some aspect of sports history, and I said, “All I know about is baseball.” I wanted to make it a seminar, seniors only, small classes. They had to write an essay to get in to the course: on anything they wanted in baseball. I taught it 10 years: “America and the National Pastime.” I taught the last class last year. I’m almost 82. It’s time to pack it in.

What important knowledge did your baseball course impart to students?

Baseball’s not just baseball. It’s integration, immigration, law, transportation, travel, Manifest Destiny, race, labor and business relations, ethnicity, technology – a whole series of topics that really represents American history. Baseball is a template to study American history. There are so many different things that are part of baseball.

You also wrote books on higher education, German literature, two books on Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem. You said you studied Yiddish and German because that was your parents’ background. How have teaching those subjects, and teaching baseball, helped you explore your own roots?

I’m not a very introspective person, so I wasn’t exploring anything with me. These are subjects I saw and thought would be interesting to kids who didn’t know anything about them. I just want to teach things that they don’t know anything about that I think are important. They don’t even know they come from immigrant roots – but everybody comes from immigrant roots, unless you’re an American Indian. I thought it was compelling to teach the immigrant experience. It starts, for the Jews, in the shtetls of Eastern Europe. They poured out from 1880 to 1920, until the two Italian anarchists – Sacco and Venzetti – held up a paymaster, and the [United States’] doors shut. I want to teach them about what’s going on now in the context of what happened then.

If I have one motto, it’s this: Nothing changes. In baseball, the basic framework of 90 feet [between bases] – once that was settled in the 1840s, it stayed that way. If I could press a button, I’d have everybody major in history. You have to know that to be educated. I threw baseball in as part of the mix. I can teach anything and make an excuse for it.

What do you recall of the games you saw as a kid?

I remember watching my first World Series game in ’47, going from bar to bar in West New York, N.J. We didn’t have a TV, and they wouldn’t let you into a bar if you were 13, so one guy said I could stay in the doorway. The first World Series game I went to was in ’52; my first game at Yankee Stadium was 1941, when I was seven, with a friend of my father: Yankees against the Washington Senators.

What was it like for you to be a baseball fan in that era?

It’s like I was on the board of General Motors. I was a Yankee fan, and they were winning World Series after World Series. It was wonderful. Baseball was my passion. There was gambling going on, on the side. I created a “six-hit pool”: betting that kids couldn’t name three hitters who would get six hits together on any given day. Each player would have to average two hits that day. I’d give them odds, and they’d bet a quarter, a nickel, a dime. They’d pick Ted Williams, Stan Musial, Harvey Kuenn, Enos Slaughter.

They didn’t realize that Williams – a .300, even .400, hitter – would often walk twice, because he wouldn’t swing at balls that were out of the strike zone. Williams would go 1-2 or 1-3, but he wouldn’t get two hits. They’d go off imperfect information, and I had better information. They’d pick guys who got a lot of hits, had high batting averages. Their players [combined] would end up getting five hits or four hits – and very rarely six hits. So, I made enough money for my first year of college! [Laughs.]

Still, that was risky for you.

I’d be risking $5, $10 a day, and I had to make sure I’d make money. It was knowing the statistics, and nobody was doing statistics except me.

So you were into OBP [on-base percentage] before that stat became fashionable.

Just a little bit. Having just that little bit of edge was enough to give me profit. And if they picked somebody who didn’t play that day, that was their problem. I ran the pool when I was in high school: ’49, ’50, ’51, ’52. I made $300 or $400. That covered my first year of tuition at Drew University. After that, I got a scholarship.

It’s very cool baseball helped get you an education – and that Drew’s baseball coach, of all people, is who told you to major in German.

It [baseball] was there all my life, then I became interested in history. I started looking back to the 19th century – that [baseball] was more than just a game. My parents were illiterate European immigrants, and were determined that I should go to college.

What book would you want to write next?

Maybe a book about Jackie Robinson after he retired. That would be a good subject. He was angry, furious, a Republican. People don’t realize what he was like then as a human being. The great post-Robinson biography has yet to be written. But I don’t have that itch anymore. I may want to write another book on higher education, because American higher education is the best-kept secret in the world. We are the envy of the world, even tough we make an industry of beating up on ourselves. We are “it” in higher education.