Norm Miller Q/A: A most interesting career; Memorable moments and encounter with Antisemitism

He was present at the opening of the Houston Astrodome (where a teammate’s boa constrictor defecated all over his uniform before the festivities); roomed with Jim Bouton while the pitcher was writing the controversial “Ball Four;” and lockered with Henry Aaron during Hammerin’ Hank’s assault on Babe Ruth’s all-time home run record.

He was present at the opening of the Houston Astrodome (where a teammate’s boa constrictor defecated all over his uniform before the festivities); roomed with Jim Bouton while the pitcher was writing the controversial “Ball Four;” and lockered with Henry Aaron during Hammerin’ Hank’s assault on Babe Ruth’s all-time home run record.

Yes, Norm Miller had a most interesting career in baseball.

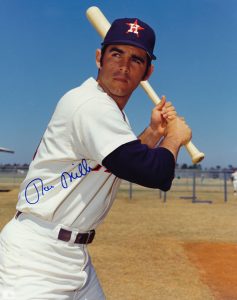

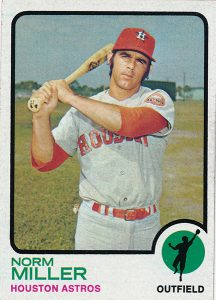

Miller was a light-hitting but hard-hustling outfielder, who finished his career with the Atlanta Braves after spending parts of nine seasons with the Houston Astros. Signed out of high school as a second baseman in 1964 by the Los Angeles Angels, Miller switched to the outfield after joining the Astros, since Joe Morgan was already firmly ensconced at second base for Houston. Typically utilized as a backup outfielder and pinch-hitter, Miller still tried to do whatever he could to inject some winning energy into his team, even going so far as to don a superhero’s cape in the dugout and dub himself “The Secret Weapon.”

Though he never racked up All-Star caliber numbers — he retired with a .238 batting average and 24 career home runs — and his propensity for running into walls at full speed eventually ended his playing career before his 29th birthday, Miller still enjoyed many memorable moments.

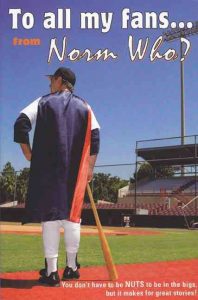

Now retired and living in Oregon, Miller — whose post-baseball career included stints in corporate marketing, sports radio, and the Astros’ organization — published a Ball Four-esque memoir of his playing days in 2009 called “To All My Fans… From Norm Who?”, which highlighted both his self-deprecating wit and his many brushes with greatness in the big leagues. It might have been greater if not for a manager who wouldn’t start him because he was Jewish.

Here is the link to his JBM player page.

******

Short Takes

On his father’s influence: “The few words he ever said had a lot of common sense to them: You will run out every ball, you will respect the game, and you’ll get out of it what you put into it.”

On Sandy Koufax: “I asked [Don Drysdale], ‘Did Koufax know how good he was?’ And he just laughed and said, ‘Let me tell you something — he never understood how anyone ever hit one pitch off him!’”

On Marvin Miller: “Marvin Miller was a fantastic human being; a nice man, a very good man, and every ballplayer should worship him every day.”

On clubhouse hazing: “Guys would tell me Jew jokes. ’And I retaliated in every way I could; I’d cut the crotch out of their suits, I’d pee in their shoes. I didn’t let up! But we all loved each other. If you were in trouble, these guys were all going to be there for you.”

*****

The JBM interview

The JBM interview

You were obsessed with baseball from an early age. Did you get the passion for the game from your dad?

Miller: Everything in my life is due to my dad. He was just the best dad, and I miss him terribly. Very quiet man, but he could hit great fungoes! [Laughs] He just loved the game; he put a glove in my crib, and I still remember how it smelled. He came home from work every night, and that’s all he, my older brother and I would do — go out and play baseball. And by the age of eight, it was becoming clear that I really did have a talent for the game.

My dad never pushed me — he didn’t have to — but if it wasn’t for him, I wouldn’t have played. I was a wild kid, a curious kid, always in some kind of trouble. But we always ended up on the little league field down the block, and that’s what kind of straightened me up, I guess.

How traditional was your Jewish upbringing?

My parents were both brought up fairly orthodox, but I refused to go to Hebrew school. The rabbi said, “Well, my wife will tutor him at home.” So at the age of eight, they marched me into the rabbi’s apartment, and it was overlooking our little league field; I never took my eyes off it for the whole lesson. When my mom came to get me, Mrs. Roth, the rabbi’s wife, suggested that we don’t do this; “We don’t think this one’s gonna take to it too well,” she said. [Laughs]

Both my mom and my dad recognized my passion for baseball at a young age. That’s a word that gets thrown around these days, but I really had it. I was very little, but I was an over-achiever, and I was determined to make it. My dad came to all my games in little league and high school, and he traveled with me for a lot of my games in the minors; he was a part-time scout for the Angels, so he knew the game. The few words he ever said had a lot of common sense to them: You will run out every ball, you will respect the game, and you’ll get out of it what you put into it.

You were the first Jewish player in Houston Astros history. Was that something that was widely known or remarked upon at the time?

No, I think the only time it ever became an issue was when Sandy Koufax took Yom Kippur off and I asked — and they said, “You’re not Sandy Koufax!” [Laughs] But in 1967, we had four Jews on the Astros, which I think was a record at the time.

Who were the other three?

A: Barry Latman, Larry Sherry and Bo Belinsky.

It’s interesting that you should mention Belinsky, because many Jewish baseball scholars don’t accept him as a Jewish ballplayer.

Well, he claimed to be one. [Laughs] It depended on who he was talking to, I guess. Okay, so we only had three and a half Jews on our team! [Laughs]

Did you, Latman and Sherry bond at all over a sense of shared Jewish identity?

I’m sure I instigated a lot of stuff. I probably told people that if they needed their money handled, we were the three guys who could do it — you know, all the typical clichés about Jews. There were a lot of Jew jokes in the clubhouse. But we were vicious human beings, back then; and when one of your teammates ripped you, you felt accepted. We’re on the road for nine months, eating breakfast lunch and dinner together seven days a week; so when you’re in the batting cage, and someone says, “Hey, Jew! Get outta there!” it’s no big deal. If you were thin-skinned, you’d better go back to the minor leagues!

But yeah, guys would tell me Jew jokes. And I retaliated in every way I could; I’d cut the crotch out of their suits, I’d pee in their shoes. I didn’t let up! But we all loved each other. If you were in trouble, these guys were all going to be there for you. There was Antisemitism, though, and ultimately I found out, 25 years after I retired, that there was a degree of that which did affect my career.

In what sense?

In what sense?

Well, I played for a manager named Harry Walker for five years, and Harry was a bad guy. At 23, there was no doubt that I had the chance to be a pretty good ballplayer. I was playing every day in 1969 and hitting .300, and then all of a sudden I was benched for a week, for no reason. Finally, I went up to Harry and I said, “Why aren’t I playing?” He said, “None of your goddamn business.” And, because this is before free agency, I was stuck playing for him for several more years.

I found out 25 years later exactly what it was about. For years after I retired from baseball, I used to stop by the Astrodome and pitch batting practice. One night, I was in the press club afterwards, eating dinner, and a fellow came in who was a retired Astros executive from the days when I was on the team. I don’t want to tell you his name — he’s dead now, anyway — but he walked up to me and said, “I’ve had something on my mind, and I just want to tell you. I was never a huge fan of yours — I thought you were pretty cocky — but I always thought you should have been in our lineup every night. The reason you didn’t play [regularly] was, Harry said to me one night, ‘There ain’t no Jew gonna play on my team like that.’”

And that made me feel okay, actually, because it was good to know that it was nothing that I did — it had nothing to do with my talent, my ability, my attitude. I was just a hardnosed ballplayer who loved to slide, loved to break up double plays, loved to hit, and loved living the life of a ballplayer! I got screwed, and I wasn’t the only Jewish ballplayer who did, but at least I could go the rest of my life knowing that I gave it my all.

At the time, how did you deal with being relegated to a back-up role?

The thing is, you weren’t allowed to wallow in it — it was all about the team. You had a job to do; and goddammit, if you’re just going to pinch-hit, be the best pinch-hitter you can be. And that’s what I did. I decided that I would wear a cape, paint lightning bolts on my shoes, be “The Secret Weapon” and drive everybody on the other team nuts. I even tried to drive everybody nuts on the bench, especially Harry, just so he would put me out on the field! [Laughs]

You never faced Sandy Koufax, but you watched him from the Astros dugout on several occasions. What do you remember about seeing him in action?

I grew up in L.A., so I watched Koufax every game I could; I’d sneak out of school and go watch. He lived in Sherman Oaks, where I lived. I remember vividly watching him pitch against us in 1966, when his arm was really killing him. He struck out Joe Morgan on a curveball; I’m sitting in the visitors’ dugout at Dodger Stadium, and I swear to you that ball dropped eight feet — and if I’m embellishing it, then it was seven and a half! [Laughs] Joe came back to the dugout shouting every cuss word he could. And I’m laughing my head off, because I don’t have to go up and face him next!

Don Drysdale was a good friend of mine — he was older than me, but we’d gone to the same high school in L.A., and we eventually became friends. We were having dinner in Houston one night after he became a broadcaster, and I asked him, “Did Koufax know how good he was?” And he just laughed and said, “Let me tell you something — he never understood how anyone ever hit one pitch off him!” [Laughs]

Koufax and Bob Gibson — to this day, I don’t think anyone has come close to those two. Except Sandy was a nice guy, and Gibson was a prick! And I played every game against Gibson, because nobody wanted to face him, and I was a left-handed hitter, so I was always in the lineup against him. And I went oh for nine years! [Laughs] The very last time I faced him, I hit a groundball to Dal Maxvill at shortstop, and he threw me out. Then I ran across the back of the mound, stopped and looked at Gibson and said, “I gotcha, you bastard!” [Laughs]

You did face Kenny Holtzman, the other great Jewish pitcher of your era — and you went 0-for-6 against him with three strikeouts. What was it like facing him?

I’m surprised I didn’t have six strikeouts! [Laughs] He had great stuff! 0-for-6, huh? Well, that’s good — at least I went up there! [Laughs]

You were on hand for the first ballgame ever played at the Astrodome, an exhibition against the Yankees on April 9, 1965. What was more memorable — seeing Mickey Mantle crush the first home run ever hit at that ballpark, or watching Turk Farrell’s pet snake take a dump in your locker before the game?

The boa constrictor! It all started with the alligators that Turk made me bring back for him from spring training — he handed me a box and said, “Rookie, make sure you bring this to the clubhouse tomorrow night,” and I look inside and there are baby alligators! He put ‘em on a leash, and he’d put ‘em in the whirlpool so nobody else could use it — they were only about twelve inches long, but they had really sharp teeth! [Laughs]

So anyway, everybody’s getting dressed for the ceremonies downstairs, and I’m running late, and I turn around and there’s a goddamn boa constrictor crawling on the floor, about ten feet long. I’m screaming, but nobody’s up in the clubhouse with me but Whitey Diskin, the old clubhouse attendant, and he’s petrified. My teammate Mike White comes in, and he loves snakes, so he grabs it — and the snake shits all over my uniform. I can’t even go out for the opening ceremonies! Of course, when they say, “You’re fined fifty bucks for being late,” you can’t tell them, “I had a boa constrictor in my locker!” [Laughs]

You roomed with Jim Bouton while he was writing “Ball Four.” Were you aware of what he was doing?

Yes. I was the first one to read it. Jim is a very interesting person; he’s not your typical ballplayer. Tough guy, nice guy, wonderful to room with, but different. Jim would come back to the room every night and he would talk into a tape recorder, and then he sent the tape off every day to his editor, and they’d send the galleys back and forth, and everything. So I knew what was going on.

When Ball Four came out, to the best of my recollection, most of the players were fine with it, because they knew Jim. But let’s face it, he’d wrote things that nobody’d ever written before. I don’t think it hurt baseball at all, I really don’t — but then again, you’re talking about 1970, and it’s hard for people now to remember what the world was like back then. Of course, the commissioner did a great job of selling that book!

It was a funny book. He made me look like a maniac — all the strange shit I did, like drilling holes in the back of the dugout and looking up women’s dresses. Hell, nowadays, if I drilled a hole in a dugout and looked up a woman’s dress, I’d be in jail! Nobody has a sense of humor about perversion anymore! [Laughs]

You were a player rep for the Astros. Did you have a lot of interaction with Marvin Miller?

Just one spring, in 1973. The Astros were going down to Pompano Beach to play an exhibition game against the Rangers, and Marvin was going to have his annual meeting down there with us — Marvin would meet with every team during spring training, but he’d do it before the games so he could get two teams at one time. But the morning that we were going to Pompano, the Astros decided not to send any of our starting lineup; I went, because I was the player rep, but they filled the team bus up with rookies and kids from the minor leagues, just so that the starting lineup couldn’t meet with Marvin — to them, he was the enemy.

Leo Durocher had been hired as our manager at the end of the 1972 season, and Leo ordered everyone to take batting practice and not go to the meeting with Marvin. So these young kids went to batting practice, but I refused to do that; I went out and sat in centerfield and had the meeting, and by dinnertime it was a pretty big national story. They held a press conference back at the Astros camp, and I was called in and asked, “What do you think about what happened today?” And I said, “Well, Leo was absolutely wrong!” And shortly thereafter, I got traded! But Marvin Miller was a fantastic human being; a nice man, a very good man, and every ballplayer should worship him every day.

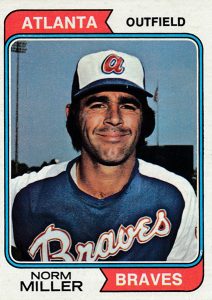

The Astros traded you to Atlanta, where you played very little because of your back injuries — but at least you got to have a first-hand view of Henry Aaron’s assault on Babe Ruth’s home run record, right?

The Astros traded you to Atlanta, where you played very little because of your back injuries — but at least you got to have a first-hand view of Henry Aaron’s assault on Babe Ruth’s home run record, right?

And not only that — I lockered next to Hank. I was on the disabled list for most of the time I was with the Braves; I tried to make one comeback, and it didn’t work. So I filled my locker with extra pencils and flash bulbs for the press — I took care of all the press during their interviews with Hank, introduced Hank to all of them. It was a very important role, but I never got any credit for it. Except from Hank — Hank would take me out to lunch. [Laughs]

A couple of years ago, my wife and I took a trip to the Hall of Fame — I hadn’t been there in forty years — and his locker is there. I went and sat in it, and I just started crying like a baby. Because I’d sat next to that locker for two years, and just admired this man so much — because what he went through has been understated, not overstated. What they tried to do to him… and he was a pure class act, a wonderful human being, and what a ballplayer!

Henry’s last night as a Brave is an amazing story. Right before the game, he said to me, “I’m hitting a home run tonight, and then I’m leaving this ballpark.” Everybody knew he was going back to Milwaukee after the season was over, so everybody’s there to see Henry; the Braves made a fortune off Henry. The Braves weren’t a bad organization — [Braves owner] Bill Bartholomay treated me very well — but Henry had a different relationship with them. So Henry goes up in the seventh inning and hits one out of the park; he circles the bases, and then he goes into the locker room. The fans are on their feet, yelling, “Henry! Henry! Henry!” I go running up the tunnel to get him, but he’s already gotten undressed and put his street clothes on; he hasn’t even taken a shower. He hands me his shoes and says, “Here — here’s the last pair of spikes I ever hit a home run in, in the National League.” And then he leaves.

So I wrapped those spikes up in a plastic bag, and I kept ‘em for years in my closet — they still had the dirt in the cleats! When I got back into baseball years later, I decided to send the shoes back to Henry. Larry Dierker was the manager of the Astros at the time, and they were going to Atlanta to play the Braves. I said to him, “Hey, when you go to Atlanta tomorrow, would you give these to Hank?” He said, “What are they?” I told him, and he was like, “Jesus, why don’t you sell ‘em?” I said, “I’m not gonna sell these shoes — what, is he gonna give me a letter of authenticity, or something?” So he gave them to Hank, and Hank remembered and thanked me. It was a great thrill for me to be the custodian of his shoes!

Dan Epstein is an award-winning journalist who has written about baseball, music and pop culture for Rolling Stone, Fox Sports, the Jewish Daily Forward and many other publications. His latest book, the acclaimed Stars and Strikes: Baseball and America in the Bicentennial Summer of ’76, is now out in paperback via St. Martin’s Griffin. His website iswww.bighairplasticgrass.com; you can follow him on Twitter at @bighairplasgras